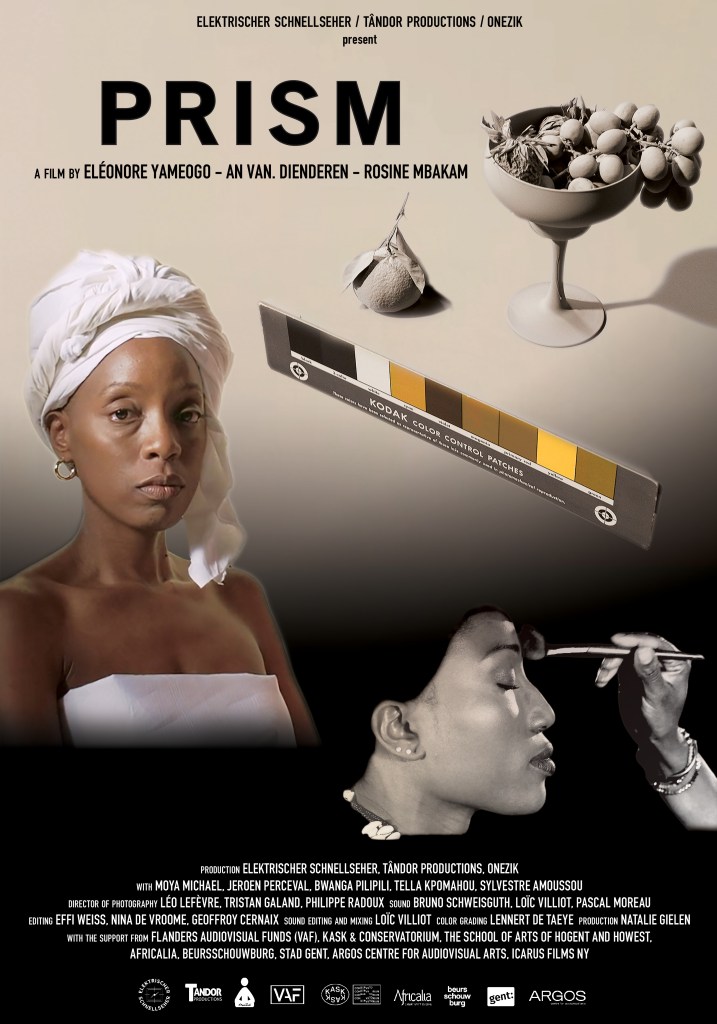

3 Filmmakers, 3 Voices

An van. Dienderen: “China Girls” are the images of white women filmed very briefly with a color card. The process is deeply hidden in the technology of cinema. Since it is only used by technicians, the average viewer does not normally get to see it. However, it is a process that demonstrates that the technology of cinema is biased to portray white skin well and the skin of colored people much worse. This is especially evident in images where you bring people with two different skin colors together. You can still see that problem to this day. Even though there are already some improvements, it still comes down to the goodwill of the technicians and of the people who have to stand in front of the camera and wait for hours until a proper, good representation of their skin color can be created, if that’s even possible. Often, those actors are also really particularly disappointed when they finally see the images of themselves: darker skin often results in a terrible mishmash of hues on the screen, with none of the hues corresponding to the actual skin color.

An: The tradition of the “China Girls” shows that the camera is not just a technology that objectively captures reality. The technology of the camera is an invention, constructed by humans and therefore not free from cultural biases. This is precisely why the “China Girls” interest me so much, and why I decided to make a film (Lili) around them.

It was striking that after each screening of Lili questions from the audience arose about how people with a different skin color deal with this built-in racism. “Are there any other types of ‘China Girls’?”; “Are there other color correction processes?”; “How do people with a different skin type cope with this unconscious racism?” I failed in answering these questions, but I found them to be very urgent and pertinent.

I thought that was a very pertinent criticism that I had absolutely no way of refuting. I had already indicated that the follow-up to Lili would be a documentary where I’m going to follow filmmakers of different skin colors in their ways of illuminating skin. But that’s still me going to make a film about “the other” as a white person. Now I wanted to approach that differently and really make a collective film. That’s when the shift came from me being the sole author to me wanting to engage in a co- creative process. Because I will never, never know what it is to have a different skin color. And that experience or that embodiment, that’s central to the project.

Rosine Mbakam: Discovering that the camera had been created with only the white skin as a reference puts me face to face with my own naivety of the colonized. I was trapped in a system where, as a black filmmaker, my main working material discriminated me. The project PRISM followed my first three feature- length documentaries. In these films, I experiment and research my gaze cinematographically. I was born in Cameroon, a country colonised by France. I was already carrying this colonial heritage in me without being conscious of it and without questioning it. I asked myself who I was and what I considered belonged to my singularity and my history, which was mostly a construction and a result of a dominant and Western ideology. The project PRISM allowed me to do an introspection and to look into my history as to what had not been influenced by this colonial past. PRISM became first of all a laboratory, where I could diagnose all that I was ruminating in silence, then a platform where, as a black filmmaker, I could share my thoughts, my resistance to this ideology, its power and everything that it unconsciously deposited in me. I finally had the space to confront myself to it.

Eléonore Yameogo: The project PRISM, which was proposed to me by An, was a surprise for me. Why is she interested in this theme? What is her point of view on how to film black people? As a black filmmaker, had I ever felt discriminated by the camera? From that day on, deep questions arose in me…

Rosine: Collaboration with the other directors takes place in a confrontation of ideas. It highlights our fragilities. I discovered a complex, that pushed me to reproduce and conform to “a story” of Africa, of the African and of the Black. When we question ourselves, it’s not always nice to see what comes out of it. It’s not nice to hear or see what I discovered in me and that I tell in the film. This process has allowed me to vomit it all up, without a filter. There I found a voice of emancipation and a liberation of my gaze. I hope that the viewer will find a way to decolonize as well.

In this quest for decolonisation, I realise how difficult it is to deconstruct an ideology when there are not many of us who think it needs to be deconstructed. Sometimes it feels like you’re always a disruptive element. It’s exhausting. But the urgency is bigger and the need is greater.

Eléonore: In my early childhood in Africa I was rocked to sleep by stories. They were stories that fed my imagination, aroused emotions, and gave me something to build on as a person. My films are built on the same principles of storytelling. The subjects of my films can be sad or happy, but all this rests solidly on a background of values that can build a person or a society. My audience is the human being, because I deal with subjects that concern people, that question their relationships with others, with their environment…

Rosine: It’s important to question oneself, to repeat this process even on things that seem obvious to us. My career has always brought me face to face with others and their differences. In Cameroon, I trained in an Italian NGO. I worked in television where I collaborated with Cameroonians, South Africans and Europeans.

I came to Belgium to study Western cinema with the conviction of returning to my country to make films. I fell in love with a Frenchman with whom I have two children. It was as if life wanted me to confront the difference of the other. When you live in a monoculture, you have to take an individual step towards the other. The different stages of my personal journey have allowed me to meet the other, to put myself in his place sometimes, to shift my gaze and discover to what extent the story of the other could be best connected.

Eléonore: The main difference between white and black skin is not due to color but rather to density. Exposure is then essential. It is the right exposure, an artistic and technical choice at the same time, which allows to reveal the beauty of black skins, by considering their tint, their texture and by taking into account a fundamental rule of black skins: its low reflection factor of the light. This reflection factor is not a racist invention, it is a law of physics (which I try to demonstrate when shooting my chapter, with characters of different colors). When we adjust a camera, we calibrate both black and white, which are, for a camera, only two electrical values (in microvolts) allowing us to analyze the energy of photons perceived by the sensor.

Rosine: It’s difficult to be neutral in today’s society. You have to get involved, take a stand, choose your side a little. Everything becomes political. While working on PRISM, I discovered myself and what I discovered was not very beautiful. I accepted it and I gave it to the spectator. I believe that as a spectator we commit ourselves by choosing the films we go to see. Those who come to see PRISM know that they will be shaken, questioned and will go on to do what they want. I trust the public.

Eléonore: There is no possibility of making a camera “that films black people better” because it would be identical in every way to those existing today. I think that we must detach the technical problem of the camera, which is only a tool, from that of the look of the filmmakers and photographers.

Leave a comment