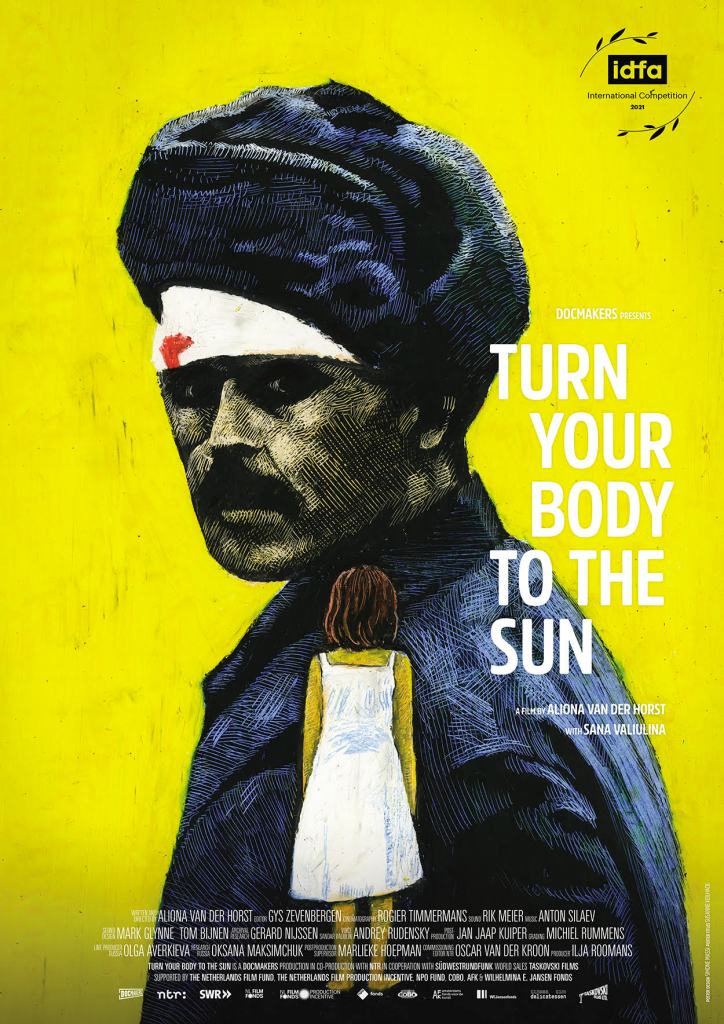

Director’s Note: Aliona van der Horst

I am convinced that Russia’s unresolved past strongly determines the present. My previous film, Love is Potatoes, dealt with Stalin’s inhuman treatment of the peasants and the resulting intergenerational traumas of my own peasant family. In my new film Turn Your Body to the Sun I take a look at another part of Russian history: the fate of the WW2 prisoners of war, but always with an eye to the ways in which history influences the present.

Sana Valiulina, the film’s protagonist, had a father who suffered an impossible fate. He never spoke about this fate during his life – it’s hard to find words for such overwhelming, traumatic experiences, and the Soviet Union’s psychological terror denied him the chance to speak out. In the narrative of the Great National war, as WW2 is called in Russia, there is still little place for the common man’s shocking, horrifying experience of war and labour camps.

Working with and editing archive footage

Most of the moving images of Soviet prisoners of war were made by the Nazis and served propaganda purposes. Camera crews cheerfully set off for Moscow to film the Untermenschen. Like an archeologist, I unearthed the archive footage and now examine it from all sides: I slow down the images, zoom in on them, replay them. I look at men who looked at the camera lens 70 years ago and now return my stare. I see their glances and try to read their emotions: is it shame, hope, exhaustion, curiosity? And in their glances I saw the reflections of Sana’s father’s glances. Thus the meaning of this enemy material changed. I think it’s important for the images to remain open to interpretation. As a filmmaker I am not going to tell you what to see in them, they are not illustrations to a story. It’s an open narrative, you have to do your own work, interpret the images and above all, ask questions – as I did and still do. And as Sana does. In the film, she says: My father is in all these images. The mass experience destroying any individuality – everything that makes you human is gone and only the basic emotions of hunger, fear, pain remain and are shared by all.

Choices of archive footage

Archival researcher Gerard Nijssen has found archive material of the Second World War: fighting in Belarus, footage of German filtration camps with Russian prisoners of war, D-Day in Normandy. The tricky thing was that I wanted to get beyond the newsreel type images, I was looking for longer, more “poetic” material. When he came across 16mm amateur color footage of the rearguard in Belarus, with endless streams of Russian prisoners of war, I suddenly saw a different war. A war which came much closer, but also a war behind the frontlines, with horses instead of tanks and unsupervised, undirected images. Some of the images of prisoners of war look almost medieval, as do the burning villages in Belarus, exactly the area Sana’s father passed through as a soldier and then a prisoner of war. The sheer rawness of these images is almost Brueghelian. I’m amazed by how strong colour, with its pictorial abstraction, affects emotional perception. The other images were colourised by an algorithm, to add consistency to the emotional perception of the film. The shades of colour aim for mood rather than realism.

Russian archive researcher Marina Drozdova found rare images of Soviet Gulag camps. They were intended as propaganda material to show the Soviet people how the “criminals” were re- educated into good Soviet citizens. But looping the images lends, for instance, a shot of men rolling huge tree stumps metaphorical overtones: it becomes a Sisyphean task, pointless and never-ending.

History is now

For so long the Second World War has been a benchmark in the lives of us, Europeans. You’d think that all the stories would have been told by now. But new stories keep surfacing. And if initially most stories were about good and evil, in these new stories there is more and more room for nuance, for grey areas, impossible choices and uncomfortable truths. This, too, is one of those stories.

Many millions of children and grandchildren of these prisoners of war are alive today. Their fathers and grandfathers were forced to continue their lives full of pent-up anger and shame, having been branded “guilty”. Some of them were finally rehabilitated a decade ago, others weren’t. Many of the prisoners of war were never found and have no names. Lately, a dozen or so small monuments have been erected in several European countries, but there is still no national monument to them in Russia. They all need one thing: recognition.

Director’s Biography

I was born in Moscow to a Russian mother and a Dutch father, and raised in the Netherlands. The Cold War separated my parents for five years, and they wrote each other hundreds of love letters during this period. In the film I made about this, After the Spring of ’68, I investigated for the first time the theme which was to reappear in different guises in all my films: how ordinary people are formed and scarred by the wheels of world politics. Making the universal visible by zooming in on the personal.

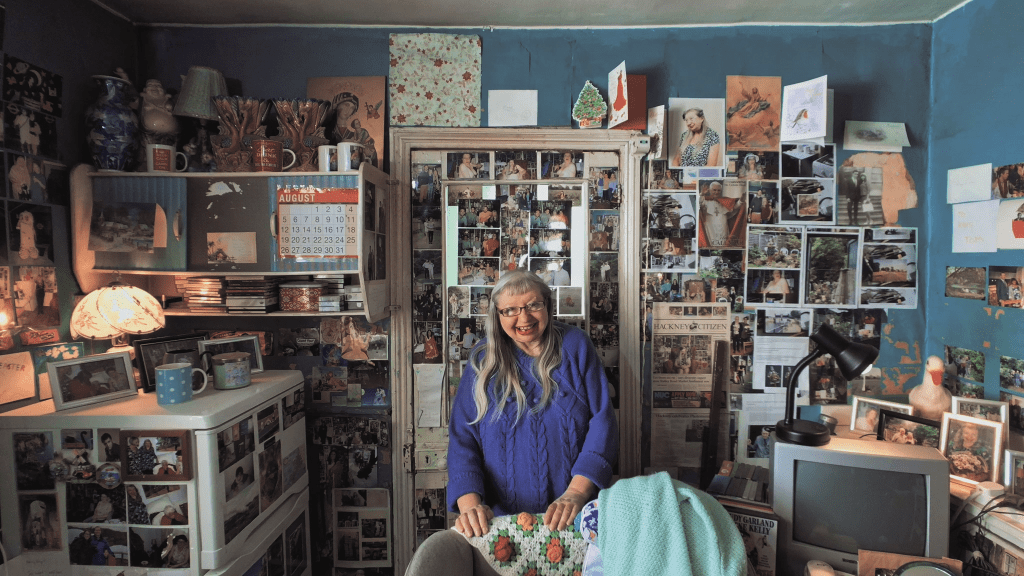

In 1988, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and this strange country of my childhood opened up to the world – and to me, an 18-year-old student of Russian literature. The Berlin Wall fell. I interpreted for Russian businessmen and once for Gorbachev and his wife Raisa. Then I went to the film academy where I graduated in 1997 with a film about the political abuse of psychiatry in Ukraine. One of the protagonists of the film told me about his father, who was one of the millions of prisoners of war starved to death by the Nazis in huge pits fenced off by barbed wire. I have never been able to forget this horrific image. Twenty years later, one film led to another, like links in a chain: I met Sana Valiulina, a successful writer of novels and non-fiction books. I admired her work, her unparalleled sense of language and imagination. Like me, she lives in Amsterdam. She told me about her wish to delve deeper into the history of the prisoners of war and to get to know her father before he became her father. Sana’s themes echo my own: parents, separated by fate, writing each other letters, today’s Russia struggling with the legacy of a cruel century. I asked her if could accompany her in the search for her father. Her journey became my journey too, and has resulted in this film.

Leave a comment