Jérémie Battaglia – Director’s Statement

I grew up in Marignane, a dormitory suburb of Marseille, in the south of France, with a population of 30,000. Throughout my schooling, I spent time with young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, many of them from immigrant families from the Maghreb. School is where I first encountered systemic racism, this feeling that the system didn’t work the same way for kids like me, from the “homegrown” middle class, and others. This reality was inescapable: these young people were systematically set up to fail by the school, social and political systems.

In the French media, there is a persistent image of young French men of North African origin as thuggish, radical, violent… As if these youths were all problematic, evil, hailing from a different culture with different values, and forced to prove that they consider themselves French, even though they were born in France. Those awful ideas are normalized and amplified by the self-indulgent social media and some 24-hour news channels. This racist vision has been polluting the collective unconscious of our country for decades, and the lack of positive role models seems to condemn these young people to constantly have to fight against these tenacious prejudices.

My childhood and adolescence spent hanging out with these young people raised my awareness of this issue. Since I turned 18 in 2001, the beginning of my adult life coincided with the rising demonization of Muslims. My friends who already struggled with economic and social challenges suddenly became potential dangers for their own country in the eyes of a section of the population.

For several years, I harboured the desire to talk about these young people, as a tribute to my friends of yesteryear, and the 2015 Paris attacks pushed me to finally do it. The stigmatization that followed took on a considerable, unrealistic dimension: in the space of a day, compatriots of North African origin were summoned to prove their allegiance to their own country.

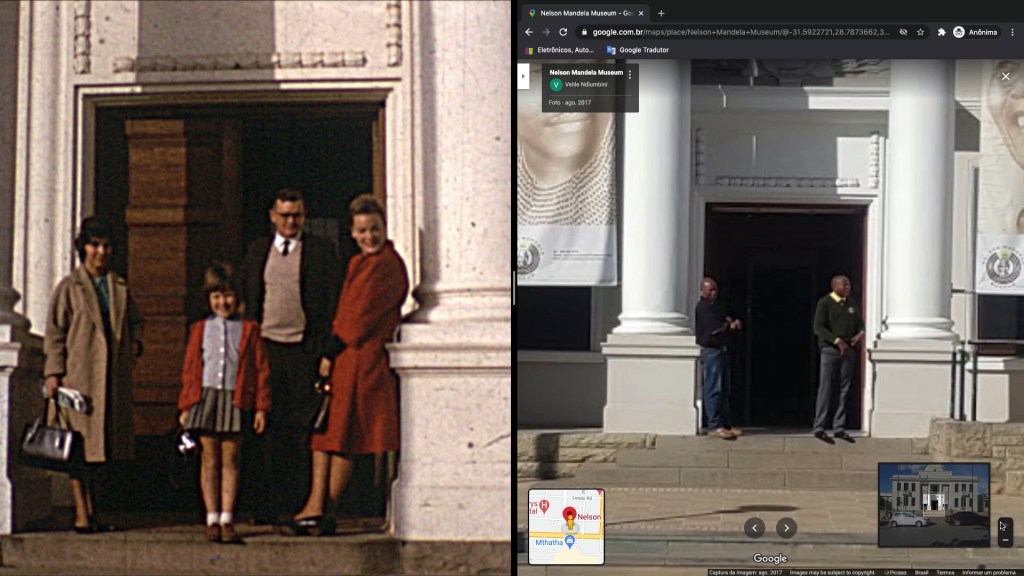

During my preliminary research, I discovered the history of Lunel, this small town in the Camargue region, where some twenty young men left for Syria to join the Islamic State. It so happens that my dad spent part of his teenage years there and that my grandparents are buried there, hence I knew the city and the region a little. I wasn’t interested in making a film about radicalization, which would have been totally counterproductive since my intention was to show a different side of this youth. But I was curious to talk to the young people who lived there, to understand how they experienced this situation. Alas, on the very first day, my research took an unexpected turn when I found myself in an arena attending a Camargue race for the first time. I immediately saw in this fight between man and beast a powerful metaphor of the struggle of these young French people.

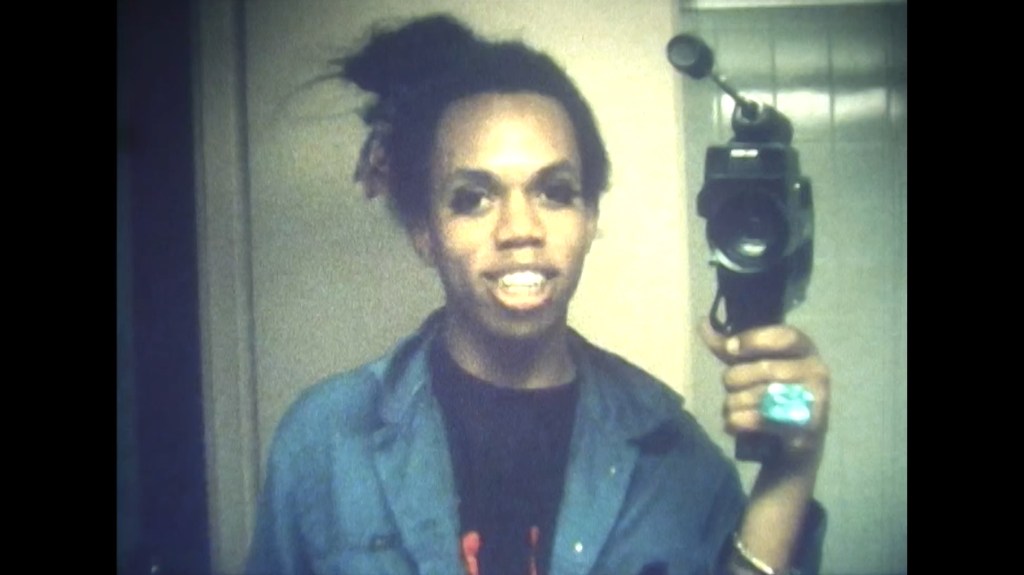

In the course of my research, I met a large number of raseteurs of North African origin. Today, they account for more than half of all practising raseteurs. There was Hédi, Brahim, Adil, Jawad, Belka… Over the many research trips and the long days in the arenas, I observed and listened to them, growing to better understand their reality, and attempting to draw a synthesis, a metaphor that would carry the film. I chose to focus on two of them: Jawad and Belka. They synthesized two different visions and approaches to the problem posed by the film: what is the price of the integration process?

For me, there’s a path that runs through my various projects, a need to take an empathetic look at my protagonists, who all have in common the fact that they are subject to strong prejudices about their life choices or origins. I’m always attracted to characters who use their bodies and self-improvement to fight preconceived ideas.

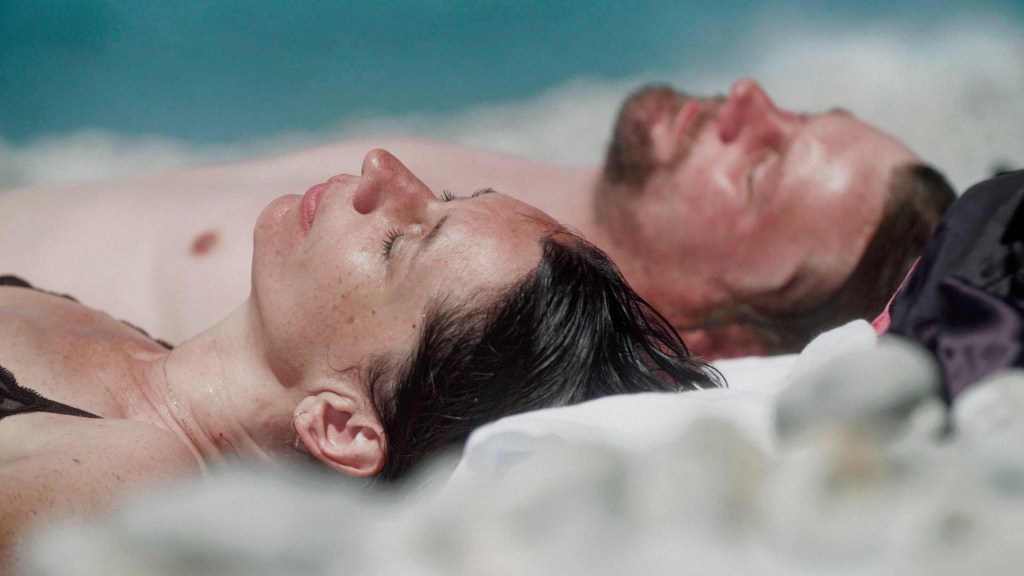

In The Brother, Fehd builds a body with extraordinary muscles to save his brother Kaïs, whose body is withering. In Perfect, the young swimmers are faced with archaic beauty standards that endanger their physical and mental health, while also confronting preconceived ideas about such a difficult sport. When the gaze of others conditions us to a subjugated social role, sometimes the only thing left is to use our body to overcome it. Symbolically, their life’s struggles are marked in their flesh by the bulls’ horns. The pressure to perform then becomes both liberating and a source of greater danger — a double-edged sword. What most interested me was the contrast between Jawad and Belka. Whereas Jawad finds some peace and keeps a wise distance, Belka is still filled with anger and stubbornness. His body is relentlessly wounded, at the risk of losing his life one day.

In a “post-truth” world, where all discussions on social networks are limited to trench warfare between irreconcilable positions, it seems more important than ever to expose myself to different life experiences, to stories that are universal in their humanity. Showcasing such stories is a political action to me. Far from the banlieues, beyond clichés, Camargue is the ideal place for an unexpected portrait of second-generation immigrants, tackling the question of their identity. Jawad and Belka are everyday heroes, for whom the Camargue races are a way to transcend the violence they’re surrounded with. The film is a tribute to their resilience. I wanted to explore the issue of racism in a thoughtful way, suggested by the characters, instead of making a militant, bullish film. Like my protagonists, I tried to make a cinematic “raset,” by addressing macro social and political issues in a roundabout way, via micro stories and very personal, very specific life experiences. More than ever, I believe in the power of storytelling, visual metaphors, and audience empathy.

In conclusion, on a more personal note, I also believe in the importance of representation. As a gay teenager, I was looking for someone who resembled me in the films I watched. Today I wonder if being absent from our media and our culture isn’t a kind of dehumanization in our society. It’s a real problem for these young North Africans. The North African man is often relegated to stereotypical parts: the thug, the comic relief or the terrorist. Without claiming to change the world with a documentary, I’m proud to offer this platform to Jawad and Belka, enabling them to present themselves to the world in their own words, through the beauty of their actions in front of the bulls and beyond the arenas.

Leave a comment