Effi & Amir – Director’s Note

Same River Twice is, first of all, a film about Israel and about Israelis. And, more precisely, about how the latter relates to the first – how they see this piece of land, what they do with it. Not during wartime – through illegal settlements and occupation – but during summertime, when on vacation.

This film is not interested in facts, in historical truths and precise details. In fact, it is full of mistakes and inaccuracies, because it is interested in how things are told and perceived – as this is what ultimately shapes our identity and the reality we live in.

It’s a lot about what is said, but also about what’s left out, not mentioned, not shown. For some, it might be surprising that the words “conflict” and “Palestinian” are never uttered – but isn’t denial the heart of the matter? We preferred to seemingly ‘go along with the stream’, with all the ‘unspoken’ that accompanies it like an undercurrent, lurking, with the absent-present quality of a phantom that emerges through hints in people’s speech , through traces in the landscape.

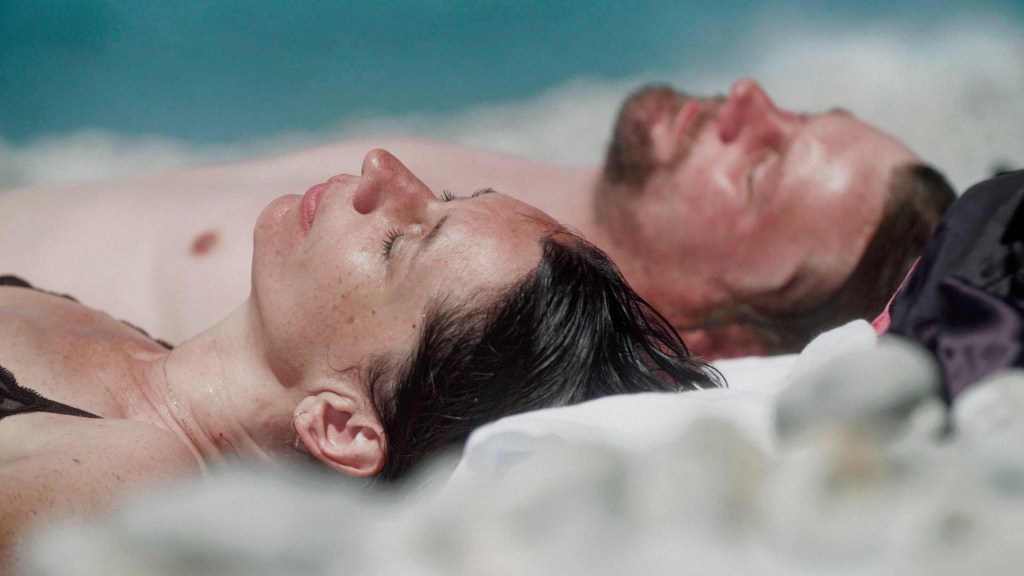

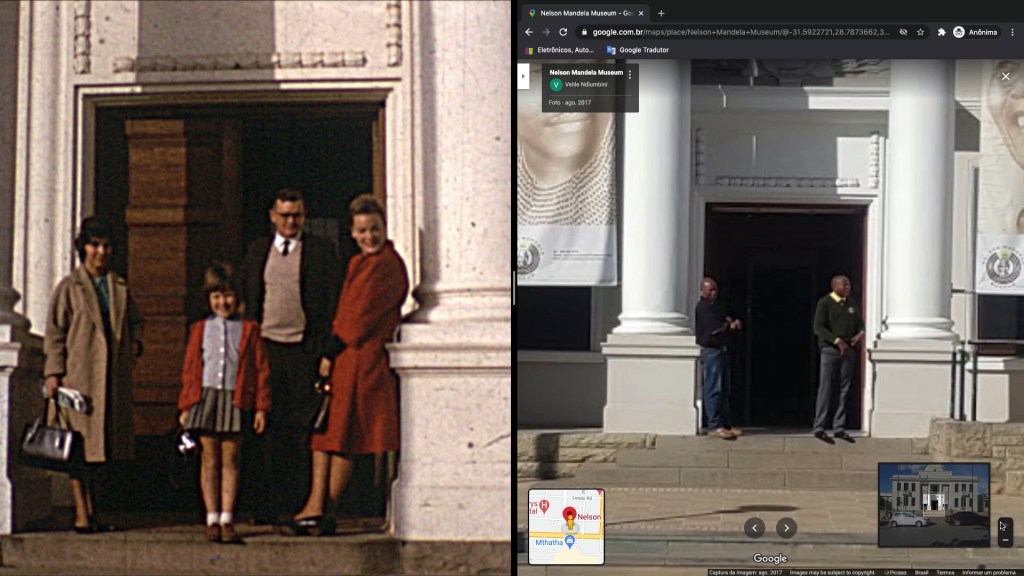

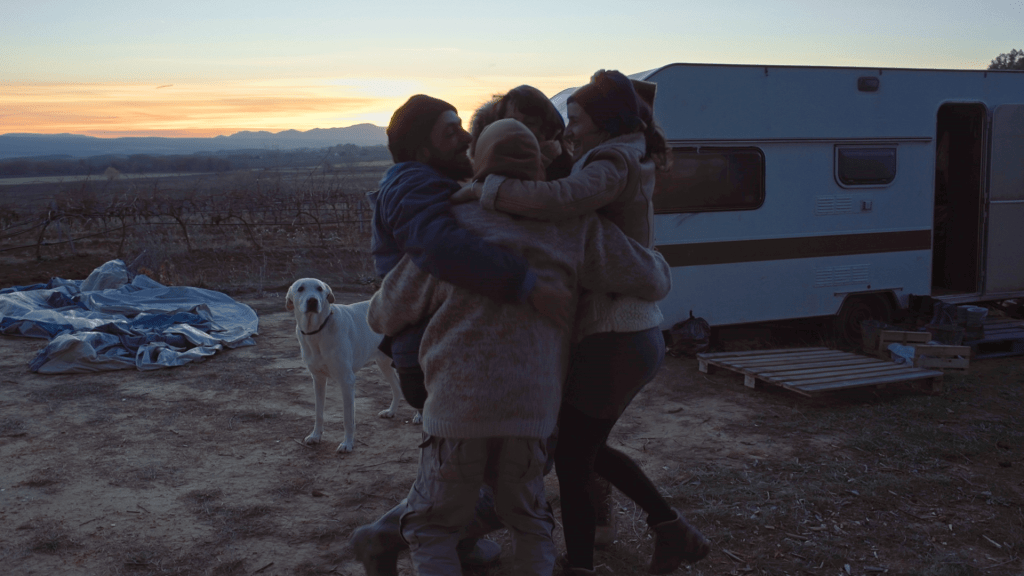

Our presence in the film, the fact that we are actually in it, is first of all our way to say that we are part of the story and not external observers, despite the importance of our acquired distance. In our encounters with our compatriots, where we play the role of the insider-outsider, the lost son or the traitor, we tried to provide enough space and reflective surface to allow for a sincere conversation about identity, belonging, collective destiny, and memory.

The reference to John McGregor, which appears occasionally in our more intimate moments and in our casual dialogues behind the camera, as well as our interference with the image of the landscape, bring in thoughts and questions about nativeness and foreignness, about the way a place is appropriated, how it becomes “known”, and to whom it belongs.

Yet beyond its specificity to the ‘Israeli case’, Same River Twice touches on subjects that are shared worldwide and are relevant to any immigrant situation, or to whoever is uncomfortable in or questions their own identity group – national or otherwise.

Why this film

Since we left our homeland in 2002, we’ve been preoccupied with the question of our relationship to the Land of Israel on both a personal and national level. Along with the physical distance, we’ve also gained an emotional and reflective one – which allows us to perceive this land as a symbolic place, not necessarily real – as it has been in the minds of the Jewish Diaspora for 2000 years.

The tension between the ‘unreal’ status of the Land of Israel, and the brave and somewhat absurd attempt to concretize it, is a recurrent theme in our artistic work of the last ten years.

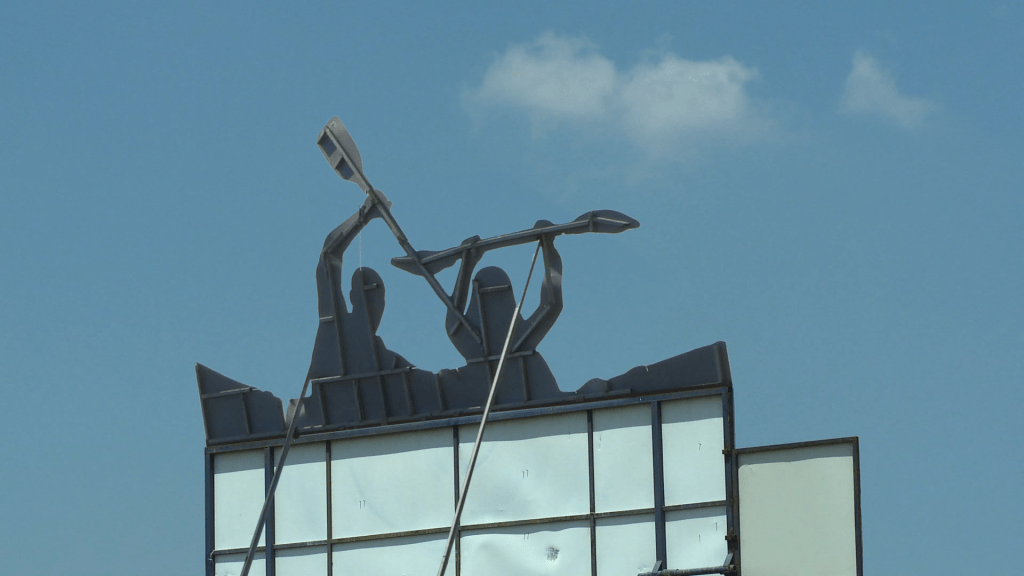

Out of the preoccupation with the Land of Israel, specifically as it were before the Jewish State (then known as ‘Palestine’), grew our interest in the 19 th century literature of travelers to the Holy Land. We were especially taken by the diary of a Scottish adventurer, John McGregor, who set out in his canoe to explore the Jordan River, from the river source to the Sea of Galilee.

On our first scouting trip in the footsteps of McGregor, in the summer of 2009, we were overwhelmed by the scale of the tourism industry and by the way that so many ingredients of the Israeli identity were manifested in this vacation setting. Bit by bit we understood that this is the filter, or rather the mediator, through which we would like to make our journey and our film. In the same way that the ‘tourism’ practiced by McGregor and his contemporaries reflected their beliefs and their set of values, so does present-day tourism tells about the society where it is practiced, about the ideologies and perceptions that constitute it.

The strategy we chose, that of an explorative journey, is not only a reference to 19 th century travel literature but also to the Zionist incarnation of the journey throughout the land as an ideological act of appropriation and self-transformation. This model of ‘domestic tourism’ on which we grew up, of “knowing the land through the feet”, had as its goal the transformation of the foreign into the local: to become the owner of the land by means of familiarity and intimate encounter with the landscape, and to rid oneself of the undesirable attributes of the ‘Diaspora Jew’ in order to become a ‘New Jew’ (strong, brave, a survivor) through the physical-mythical contact with the land.

The journey, both as a cinematic genre and an educational-ideological apparatus, introduces an element of risk, a fragility we preserved throughout the film-making process: placing ourselves in the role of the traveler, we left open the possibility of changing our own position. Are we strangers enough to be transformed by the journey?

Leave a comment