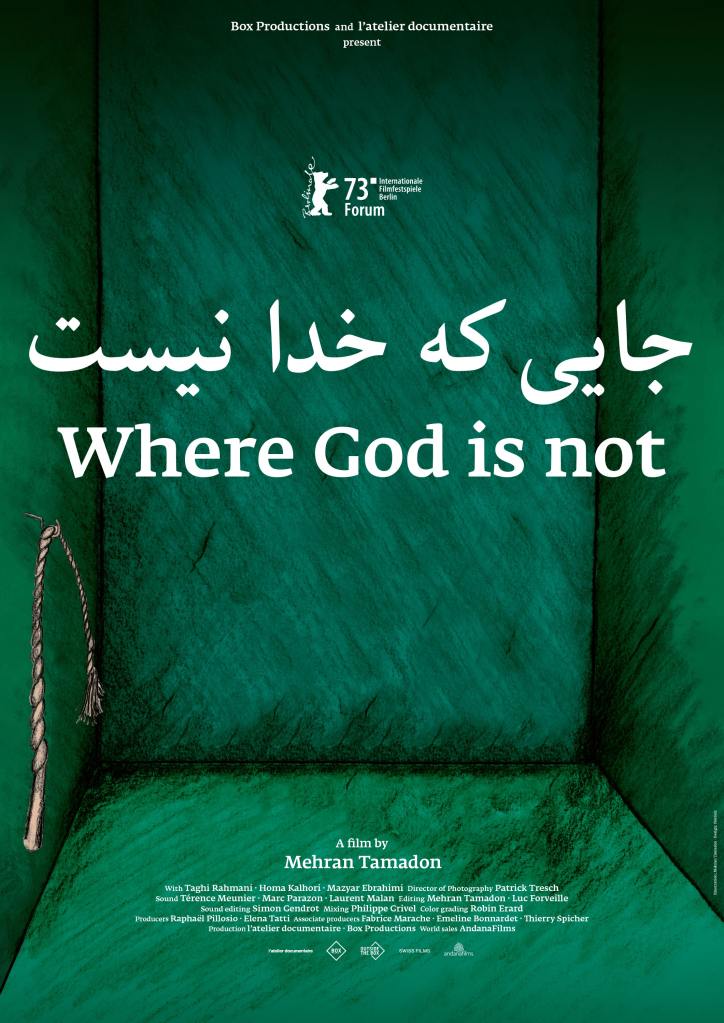

Interview with Director Mehran Tamadon

You made Where God Is Not at the same time as My Worst Enemy. The two films are different but at the same time there is a resonance between them. Did you have the idea of making two films from the start, or was it a decision you made along the way ?

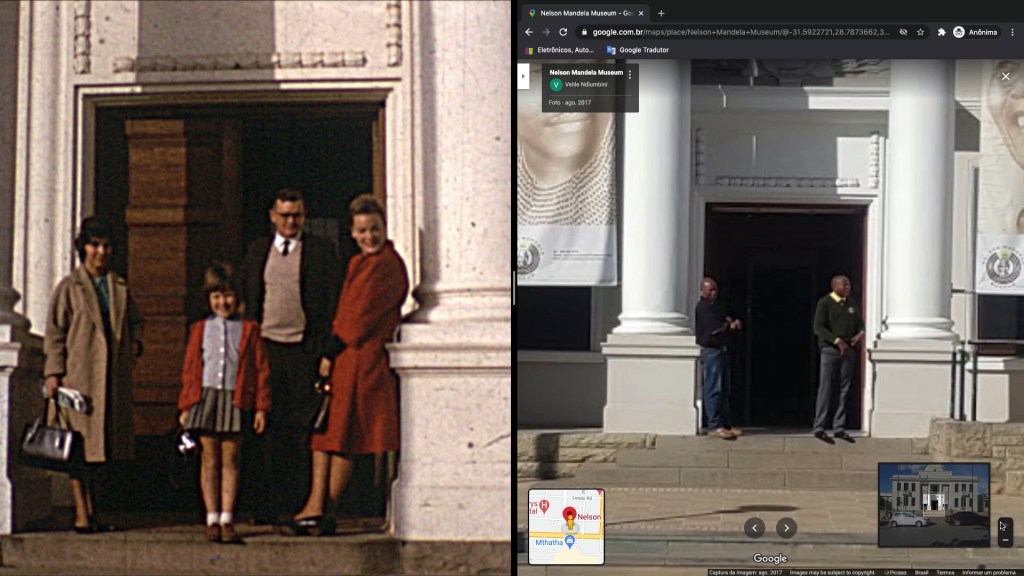

The idea for My Worst Enemy has obsessed me for seven years ! I wrote it between 2015 and 2017, the writing was a complicated process in every respect. My producers then submitted it to funding committees and we soon managed to raise the money to make the film. But the way the film was structured was so twisted and complicated that it took me two years to dare to start shooting, which happened at the end of 2020. Then the editing was so laborious that I had to stop. It was during this interruption that I wrote, filmed, and edited Where God Is Not. This allowed me to better understand what I was looking for in My Worst Enemy and to finish editing that film. The shooting of Where God Is Not shook me deeply. I was deeply moved by the stories of the people I was filming, by their humanity and strength. Where God Is Not is a relatively classic documentary in its form, but the experience of filming was necessary to allow the ideas I had begun to develop seven years earlier to mature. Chronologically, I filmed My Worst Enemy first and finished Where God Is Not first. I now consider Where God Is Not as chronologically preceding My Worst Enemy.

How did you meet the protagonists of Where God Is Not ?

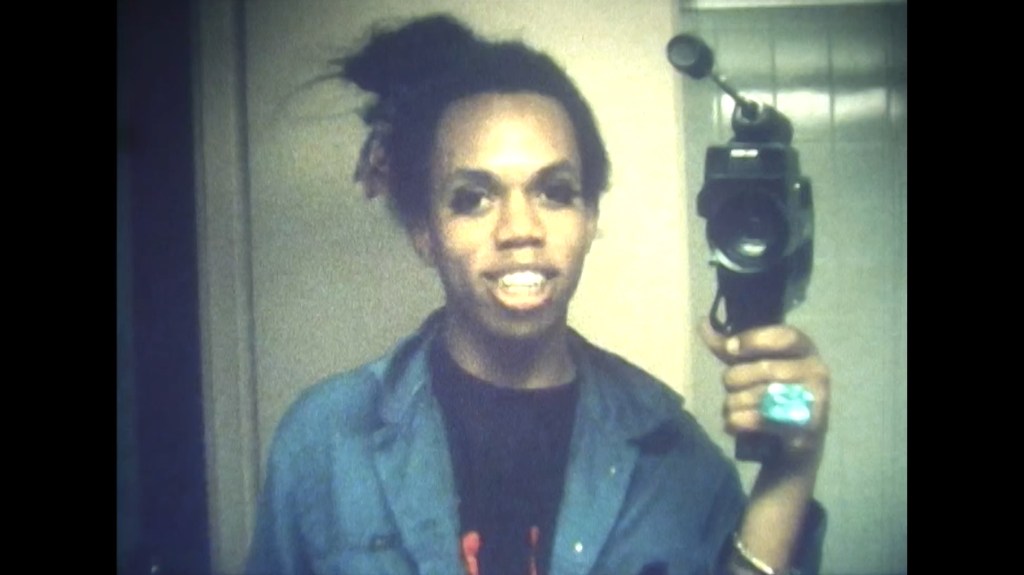

When I was preparing My Worst Enemy, I wanted to bring many exiled Iranians who were living in different European countries to Paris. But COVID limited my choices to those living in France. Later, for Where God Is Not, the lockdown was over, but by then I had already chosen my protagonists. From the beginning, I had decided to film only Taghi Rahmani who lives in Paris, Homa Kalhori who lives in England and Mazyar Ebrahimi who lives in Germany. They each have different backgrounds and even if they are all opposed to the Islamic Republic, they do not necessarily share the same political convictions. They were also subjected to prison and torture in different periods of the Islamic regime. They reacted differently to the violence they were subjected to, each developing different survival strategies. Their stories, their ways of reacting to the camera, their way of appropriating the re-enactment process allowed me to build the narrative of the film.

What was it about their prison stories that appealed to you ?

In my initial discussions with Mazyar Ebrahimi, he asked me to reconstruct the torture chamber. Having never seen a torture chamber, I didn’t see how I could make it a reality in a documentary setting. So, I proposed to reconstruct it and to design it like a theatre set while filming it. Moreover, when I went to meet him in Germany to get to know him better and to suggest he take part in the film, I immediately realised that he would be a good film character. I got to know Homa Kalhori through her book in which she recounted her prison experience in the early 1980s. She was then part of the “Raheh Kargar” left wing movement and was arrested at the same time as many of her comrades. A few years later, under torture, she gave in and recanted. It was this change in political affiliation that firstinterested me in her story. I was looking for someone who could help me understand how one could change sides. As I was building the film’s narrative other questions arose. A film is also based on emotions, not just discourses.

Finally, Taghi Rahmani brings real energy to the film. When we are at the end of our tether with Homa and Mazyar, Mr Rahmani shows us through his body language and his words how he tried to resist while in isolation. Taghi Rahmani, whom I had not met before making this film, has since become a close friend. He took my questions very seriously and answered them with great transparency and kindness. The passages where I ask him about the psychology of the torturer could have irritated him and he could have answered me disdainfully. But this was never the case, he always considered my questions thoughtfully and answered with humility, as if calling himself into question, without ever being scornful.

How did the cinematic stratagem you devised for the filming affect your protagonists ?

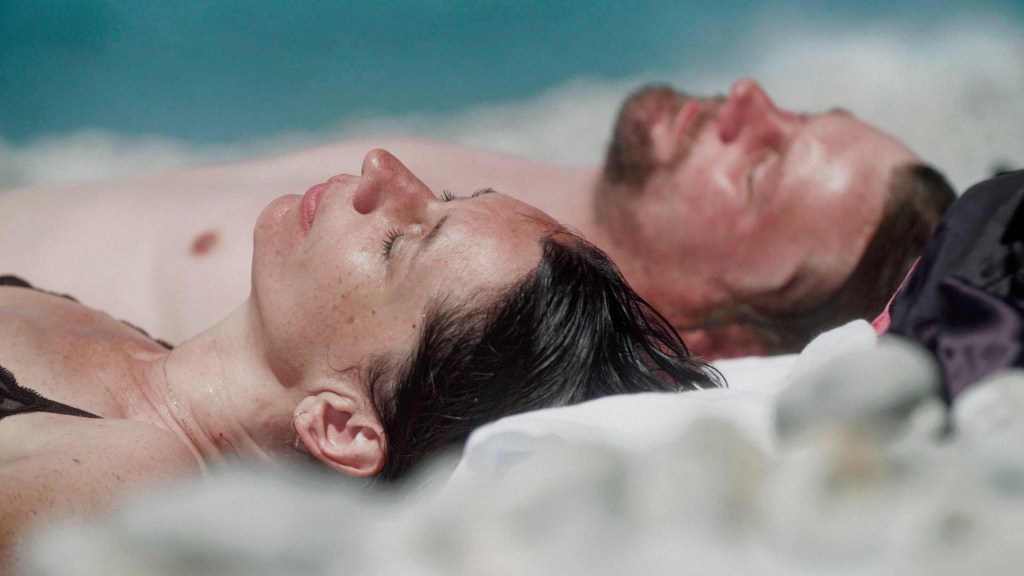

They each reacted differently. Mazyar Ebrahimi had been blindfolded when he was tortured. He therefore was unable to see his surroundings at the time, which was frightening. By reconstructing the place, he finally got the impression that he was seeing what had happened at the time. He told me about a feeling of fear that was leaving him at last. However, early in the morning when we arrived at the location, he had a very bad headache and was nauseous. It was after a few hours, when hehad made the bed and hung the chain, that he finally felt he understood what had happened at the time. The re-enactment calmed him down. It was the same with Homa Kalhori. Even though she had already published a book in which she had revealed her feelings, written about her shame, and explained why she had given in, it seems to me that making the film was also a cathartic experience for her. Because telling the story in front of the camera, something which scared her very much, was different from telling it in writing, in a book. It even seems to me that, for Homa, the process of making the film did not end with the actual shooting of it. She was finally acknowledging publicly, openly, what happened at the time and this burden she had carried since then.

For Taghi Rahmani, it was quite different. Prison is not ancient history for him. He is still a political activist. He has served fourteen years in prison. He is still considering going back to Iran, although he knows that if he goes back, he will be imprisoned. Pacing in front of my camera in a cell for him is all about what could happen to him tomorrow. His wife is still in Iran, she is currently in detention over there, as are many of his friends. For him, replaying these scenes was not therapeutic. Him acting out these gestures is a form of militant action, he is denouncing them, but he is also in suffering.

We see in the film that Homa Kalhori resisted against re-enacting certain scenes, as did Mazyar Ebrahimi, who was somewhat upset to see you lying on the bed. Did you hesitate to ask them to re-enact the scenes ?

It’s true that what I’m proposing is delicate and the question is raised in the film. In my films, I always try to put into perspective the ethical questions raised by my filming approach. With Mazyar Ebrahimi, we progressed gradually. There were frequent pauses during which he would tell me whether he wanted to stop or to go on. I kept one of these moments in the editing. I rather had the impression that what disturbed them most were the unspoken words, the silences, the things imagined. It seemed to methat telling, showing, replaying helped them to better cope with the traumas. The people I filmed live constantly with the memory of these scenes, with these experiences. I hope that I have helped them in some way to express emotions that were locked inside their bodies, in their souls.

What effect do you think My Worst Enemy and Where God Is Not might have on the agents working for the regime in the current situation ? Would they understand the reflective dimension of these films ?

Mazyar Ebrahimi says that the interrogators and torturers will see the films, especially after the exposure offered by the Berlin Festival, and I am also convinced of this. I would say that today, in the current context and given the degree of violence and repression, I don’t think it is possible for them to understand the reflective dimension that these two films offer. But maybe it will be possible in six months, or later, who knows ? Films can tell us one thing today and something else tomorrow. In any case, I made these two films so that those who defend the regime through violence would see them. I constantly imagined the torturers alone in front of a screen, watching these films. Many of the questions I ask my characters in the film concerning the torturers’ consciences are addressed directly to the latter. And my hope is that they will be somewhat shaken, frightened by themselves. Maybe the day after the screening they will get up and go back to work as if nothing had happened. Or maybe this will sow a seed that will germ later. I can only speculate. We all make assumptions based on our perception of humankind, our optimism, our belief in the power of images and cinema. The viewers will have their own answer. An answer that also speaks about each one of us and not just about the torturer.

Leave a comment