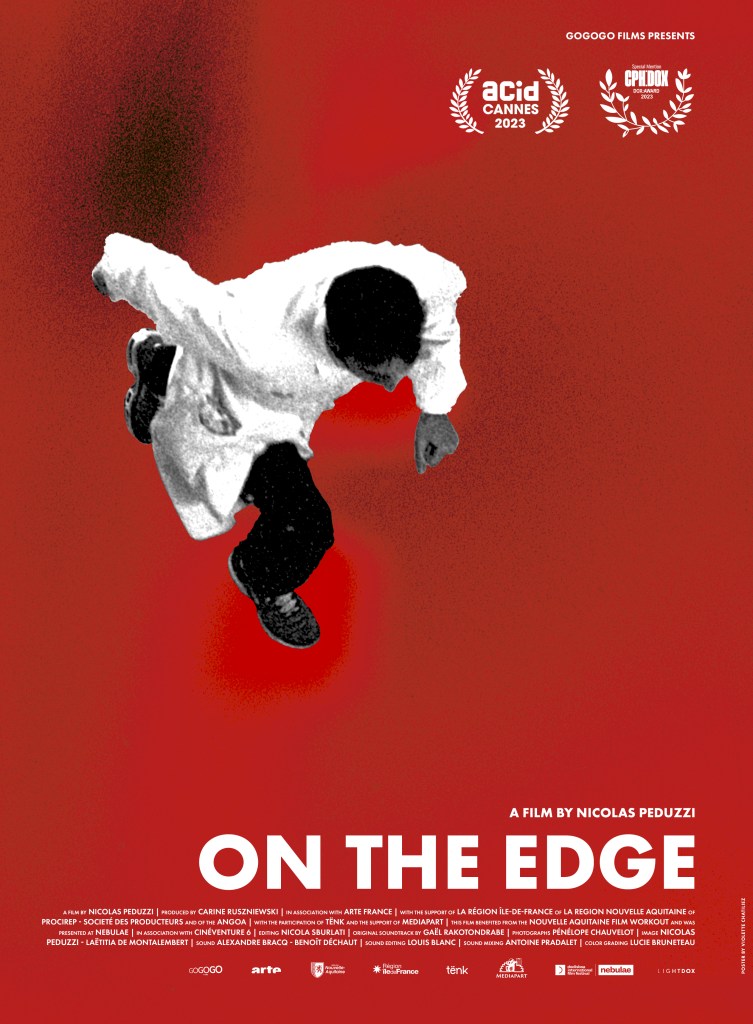

Nicolas Peduzzi – Director’s Statement

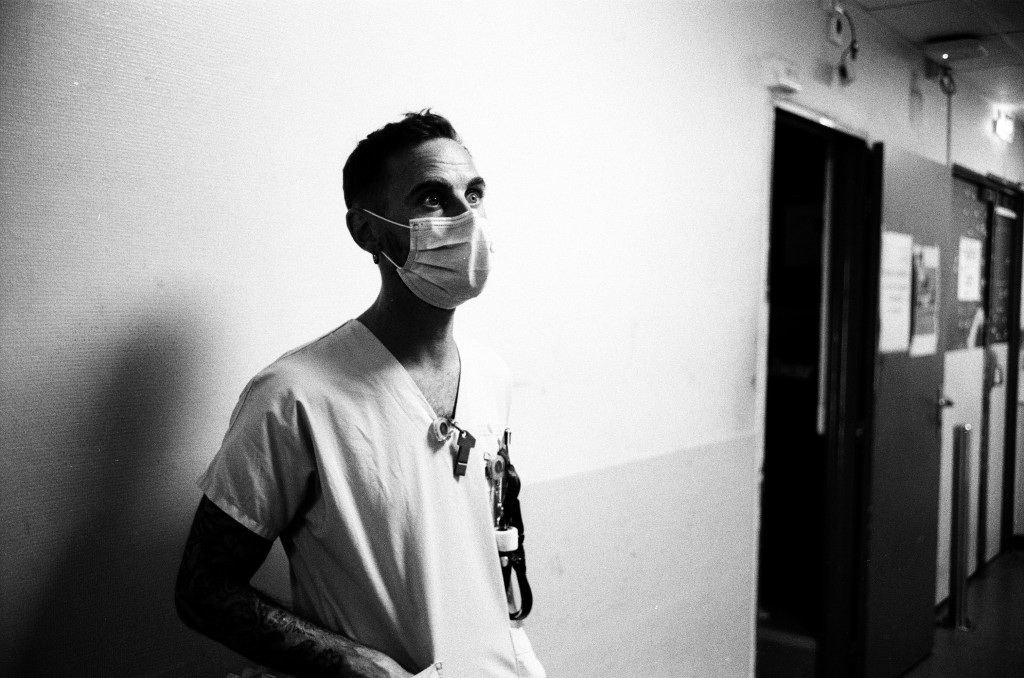

The French public hospital has always had a friendly face for me: it was the hospital that saved my father in 1990, the hospital that welcomed and supported me in the psychiatric ward when I needed it. Four years ago, the health crisis revealed the extent of the malaise in the institution, but the causes of the gangrene were obviously deeper. I wanted to question them, to understand where and how the breach had opened, and I began to film the daily life of the caregivers at Beaujon Hospital. There, I quickly met Jamal, an indispensable and controversial figure. Indispensable: he was the only psychiatrist in the hospital; controversial: despite his youth, despite all his love for the hospital, he works against the drastic changes in the institution, which are in direct contradiction with his humanist values. Every day, with his sneakers on, he climbs and descends the iron stairs, running from one department to another and from one bedside to another. Jamal is Sisyphus, and Beaujon is his mountain.

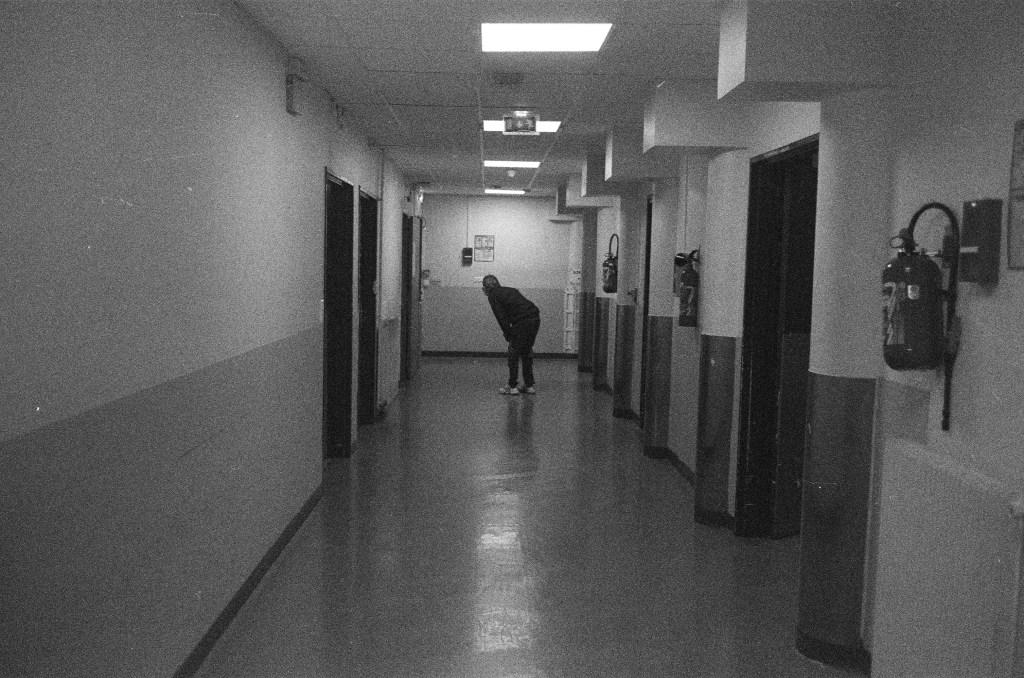

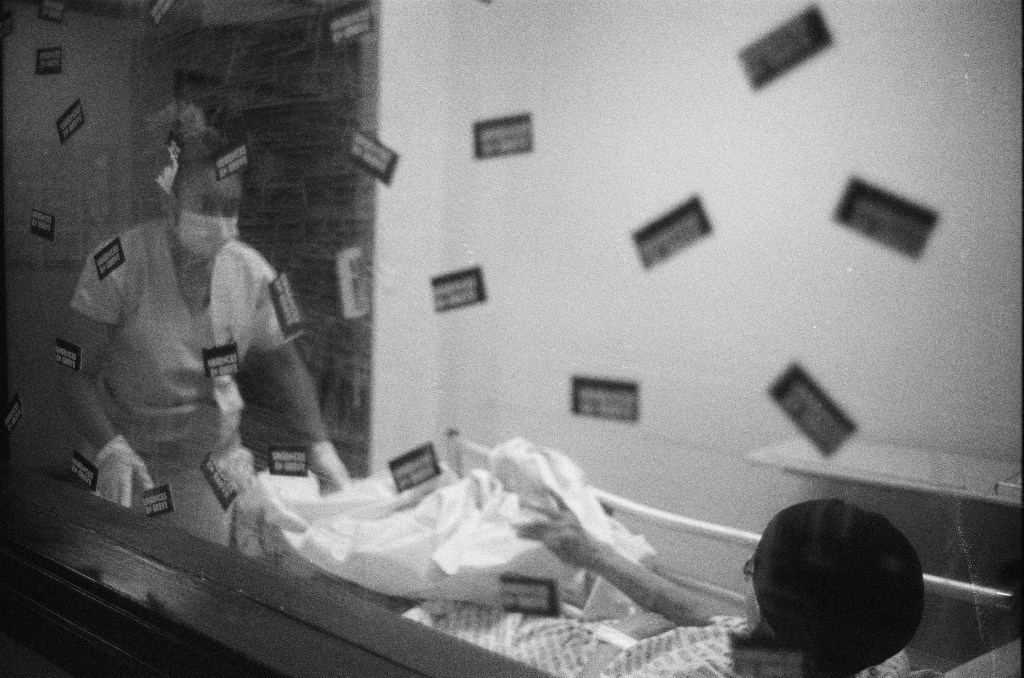

Our first contact was head-on: in the midst of the Covid crisis, Jamal was suspicious of journalists. I had to prove to him that my approach was not journalistic. So I took up residence at Beaujon to accompany his doctors and patients over the long term. This is what convinced him: time is Jamal’s main concern. In an unreasonably fast-paced environment that buries people under the numbers, he makes it his duty to take his time with his patients and their loved ones and offer them the attention and care that no one else is willing or able to provide. He soothes, reassures and guides with infinite patience. One of the challenges of the film, for me, is to bring together these contradictory timeframes: on the one hand, the frantic rhythm of the hospital, in a permanent state of emergency – long, overcrowded corridors, hasty conversations, the cries of patients demanding attention; on the other hand, the bubbles of time that Jamal creates for his patients, impervious to the chaos. Jamal devoted a lot of his time and energy to his patients, but also his colleagues during the period of Covid, and some of them have kept the habit of opening up to him about their problems. The film also includes the voices of Romain, a caregiver, Alice and Lara, the interns who assist him on a daily basis, and Ayman, a former patient who has become a trainee.

All of them share the same vocation and speak of their love of providing care, but also of their vertigo when faced with the suffering of patients, their own discomfort, their doubts and their aspirations.

Jamal and his interns are the only doctors at Beaujon who circulate in all the departments. Through them, I had access to the whole hospital. Everywhere the same observation: lack of funding, beds, personnel and time. Many shortcomings could be blamed on the lack of attention. This is not the case: every day, the caregivers at Beaujon Hospital strive towards the humanist ideal that led them to become involved. However, not everyone is ready to sacrifice their life and health on the altar of their ideals. Jamal is a character in a class of his own, out of the ordinary, Dostoyevskian, someone who substitutes the world as it is for the world he would like it to be. The problem is that reality threatens to catch up with him. It was his body that first gave the alert: a lower back pain set in over the weeks. And with the pain comes doubt. The film lifts Jamal’s mask of confidence to reveal his doubts: it sometimes seems to him that the lines will not move fast enough, and that exhaustion, loneliness, lack of recognition and discouragement will eventually get the better of his vocation.

The film tells of the strength of his idealism, but we understand that Jamal must accept the limits of his humanity. When Jamal is at the bedside of his patients, I collect their testimonies. I am sympathetic toward troubled personalities, and I share Jamal’s idea that the measure of a society’s dysfunction is the way it treats its ‘‘crazy’’ people. After two previous documentaries on troubled characters in the United States, On The Edge gives voice to the suffering of people who turn to hospitals for help and whom our French society fails to see. Beaujon Hospital is a territory as difficult to access as the suburbs of Houston, and the neuroses of both sides resonate in unison.

In general, I am concerned about the treatment of mental health issues in France. Misunderstood by some, denigrated by others, psychiatry is essential to the development of our society. The discrepancy between the fragility of patients and the rigidity of the institution, which is too bureaucratic and too protocol-based, is intolerable. Finally, it is intolerable that doctors have to take on the overwhelming task of caring for people whom society has driven to insanity.

Leave a comment