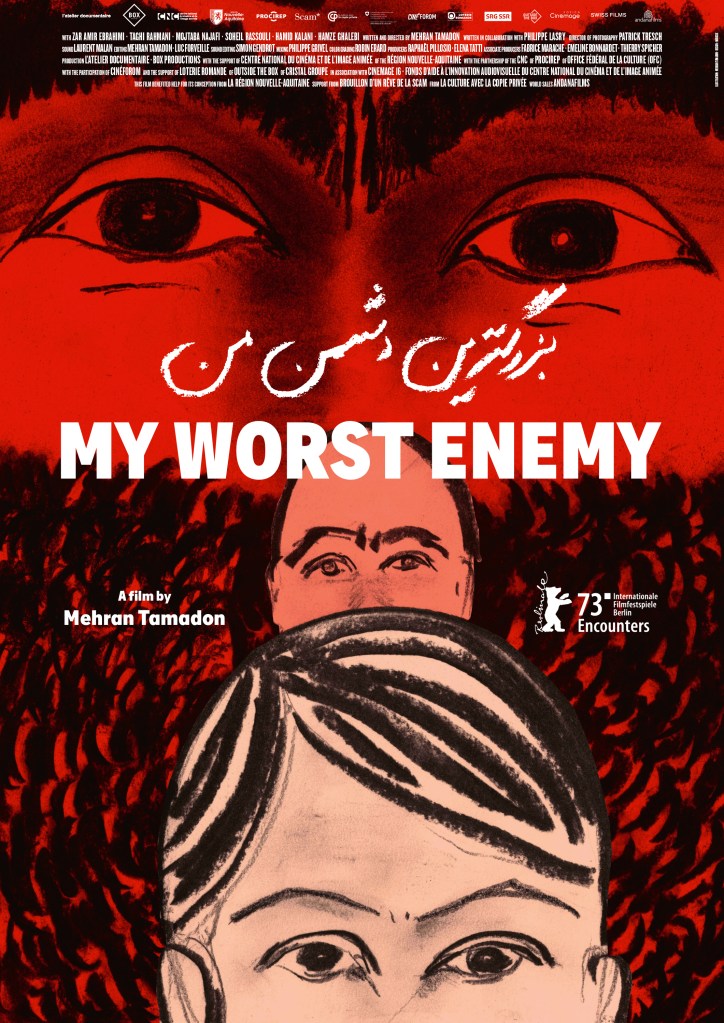

Interview With Director Mehran Tamadon

Mehran, let’s start by situating My Worst Enemy in your career. As in your previous films, namely Bassidji and Iranien, it seems you aspire to engage with people who are very different from you, with people who could harm you. My Worst Enemy has been released at a politically complicated time in Iran with many Iranians having lost all hope of dialogue. Based on your opinion and what you have learned by making your films, do you think dialogue remains possible?

In principle, people dialogue to understand one another better and try to agree. Perhaps the question of dialogue should be considered differently today. Given the brutal repression that Iranians are currently experiencing, it would be difficult to reach an agreement on anything with the people who support the regime.

Looking back, I wonder if in my previous films I was truly engaged in a dialogue that attempted to agree on anything. I’m not sure. I would say, however, that I was trying to establish a relationship in the hope of moving these people. I’m convinced that this was useful. I’m not necessarily seeking a dialogue to agree politically, but rather trying to establish a relationship to achieve acceptance and tolerance. Is this relationship still viable ? Is it possible to move such dangerous and violent men ? Undoubtedly it is, but we have yet to find the key to open their doors, which are intensely locked.

For My Worst Enemy, my initial idea was to film a final sequence in Iran. Up until June 2022, I had hoped to go there and take the time I needed to locate the interrogators working for the regime and to convince them to participate in the film. But for many reasons, I gave up this approach.

In my films, I tend to work with living material, in other words, I question the relationships and conflicts between people at a given time as they occur. The present situation in Iran is continuously changing, therefore, it repeatedly calls into question the initial idea behind the film. That’s why I don’t quite think the same way when I write the script of a film, as when I shoot it, edit it, or show it to the public. This is because the social context is never quite the same. This is enriching on a personal level but makes it difficult to build a consistent approach. I finished editing My Worst Enemy before the ” Women, Life, Freedom ” movement began in Iran. During this period, I experienced anger, hatred, and a desire to take up arms. Since September 2022, I have felt like doing many things rather than creating any bonds. Despite that, deep down I have principles that urge me to try to meet other people half-way.

Your intention therefore with My Worst Enemy was to confront the torturers in Iran with a kind of re-enactment of their actions to disturb them ? However, it seems your characters do not share your point of view, in the same way that your film does not reveal such optimism.

What I constantly seek to do is to create a bond and initiate a relationship. Now that I live far from Iran, my main way of interacting with these people is to make films in which I give them an existence and to address these films to them so they may recognise themselves. My aim with this film is for it to be seen by the interrogators and torturers working for the Iranian regime. How could it affect them ? I don’t know. They may never change. I don’t know what goes on in their minds. I only know what goes on in my mind which makes me think that other people, whoever they are, must have a conscience, as I do, and that they are also affected by conflicting feelings. They too, suffer from a form of cowardice, deceitfulness, and perversity. If I can succeed in grasping my own contradictions, I can give them the chance of discovering their own.

This is my view, but I know that few people share it. Even the people I film don’t believe it. My films are not there to prove I’m right but rather to raise questions and bring to light different paradoxes. Each spectator, each character, interpret my ideas in their own way and if they disagree with me, that’s completely fine. I don’t seek to be right, neither in my films nor when I discuss ideas. I accept being contradicted, being destabilised by the characters in my films. I think in my films that’s what I’m best at : getting people to question themsleves.

Let’s talk about Zar Amir Ebrahimi : she is a key figure in many sequences in the film. How did you come to give her this role?

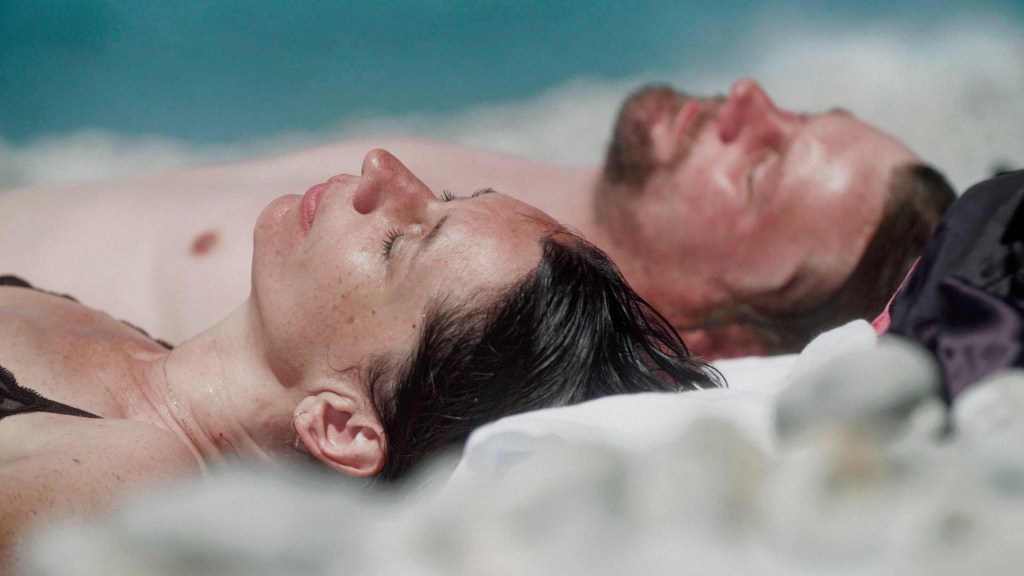

Zar plays an essential role in My Worst Enemy. However, this was not the initial plan. As you can see at the beginning of the film, I meet several former Iranian political prisoners, mainly men, with the aim of choosing one who would be willing to interrogate me in front of the camera. Among the refugees I met, Zar was one who had undergone very painful and lengthy daily interrogations during more than a year, without being imprisoned. At the end of each day of interrogation, she was allowed to go home. It was during the shooting that I realised her acting skills enabled her to overcome the psychological problems that could be brought about by the role I was asking her to play. Moreover, my films, to each their own degree, all have an introspective dimension to them. Each time, I am led to being self-critical and to calling myself into question in front of the camera. Zar pushed me in that direction by referring to the total power of the director and what he puts his characters through to achieve his ends. These questions are important in my filmmaking and Zar was astute enough to understand this and was able to destabilise me.

That’s true, we end up in a situation where the spectators doubt what they’re seeing is true. The limits between reality and fiction are blurred and we wonder whether what we are seeing is improvised. That’s the sign of a special form of documentary, and I would like to ask you about the creative process and what it managed to produce.

Two days of interrogation by Zar produced approximately twenty hours of footage. The director of photography, Patrick Tresch, filmed two hour long shots without interrupting us. Nothing had been written even though Zar had investigated me and prepared questions I didn’t know about. But you spoke about doubt : it is precisely the emergence of these doubts that is at the heart of the film. We no longer know what’s being acted out or what’s real. Is it Zar the individual speaking or is it Zar the actor? I have the impression that I am a documentary character, that Zar is a fictional character, and that reality gradually catches up with her drawing her into the documentary. But the doubts also reside elsewhere : who is the torturer in this story? Is it her or me? Zar interrogates me, but I’m the one torturing her. The beauty of documentary is that it doesn’t necessarily lead to where you imagine it will when you write it, and that’s just even better.

*not available North America, France, Switzerland

Leave a comment