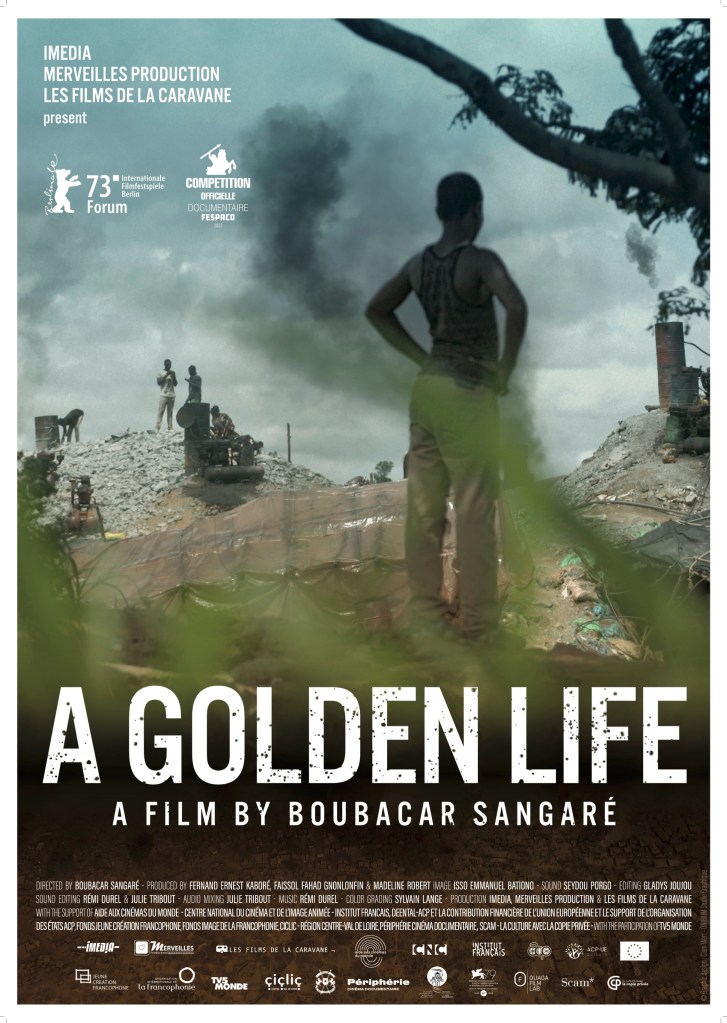

Boubacar Sangaré -Director Statement

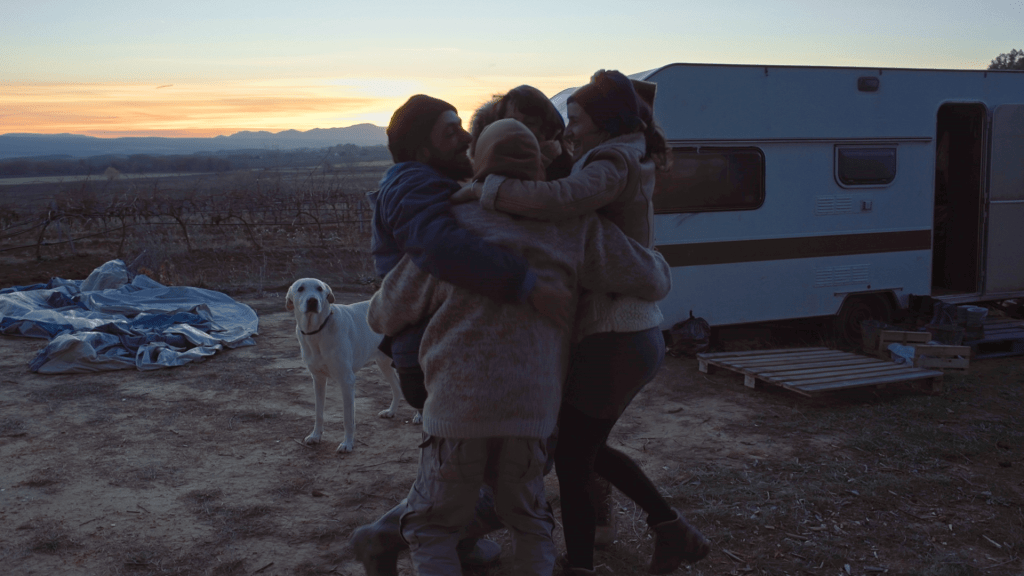

In 1996, after my CEP exam (primary school certificate), my brother and I went to work on a gold mining site. More than 22 years later, I returned to tell the story of Rasmané, Missa and Dra. Through the story of these three characters, A Golden Life paints a portrait of a whole generation of Burkinabe youth, who suddenly go from childhood to adulthood, from carefree living to violence, leaving in their wake golden dreams covered in dust. I filmed Rasmané, alias Bolo, from the age of 16 to19, as he changes in the environment of the galleries, as well as in the “yaar” where he meets Missa and Dramane, aged 12 and 13. In this universe, destinies are similar and futures seem to follow the same paths.

Around the galleries, still shots capture the daily life of this playful and dreamy character. Little by little, the wide opening on the site reveals the similarities that characterise the gold miners in their dreams and work. Just like the nature that surrounds them, innocence and dreams crumble before the unfolding ordeals. The duality between the yaar and the gallery is matched by that of the depths of the gallery and the outside of the site, to translate the effects of capitalism that confront the exploited and the exploiter, as in the sequence where Bolo’s team worries about being chased out by the prospecting “white man’s machine”.

The transformation is at work, its effect upon the bodies is felt, Rasmané does not understand why he is already suffering from back pain at his age. Are dreams but a cloud of smoke like the one that rises from the site’s central fire?

Rasmané, nicknamed “Bolo”, Gold Digger

Rasmané is 16 years old and comes from Gourcy, in the north of the country; far, far away from the Kalgouli site where he works today. Of Peulh origins, he arrived on the site at the age of 16. He is the eldest son of a family of five children. His grandfather has always taken care of him, his parents having gone to work in the capital of Burkina, his father as a driver, his mother as a housemaid. He decided to leave school and follow his cousin Sambo into gold-digging, against his parents’ advice. To a fellow gold miner who pulls his ears, Rasmané likes to retort: “It’s because of pulling ears that I left school”.

His mother and father would like him to go back to school, but their opinions have little influence on Rasmané’s choices. They don’t have the money to support him. So Rasmané decided to take matters into his own hands, to forge his own destiny, like the thousands of children who have come to try their luck on the artisanal mining sites. The promise of a better life outweighs all the difficulties.

Missa & Dramane, Friends and Cart Drivers

Missa and Dramane are 12 and 13 years old. They come from the same village, Loropéni, not far from the yaar of Galgouli, near Bantara’s mines. The two friends are inseparable. They alternate between harvesting cashew nuts for their parents and spending long months at the yaar. They prefer the yaar, even if the work is hard, because the money comes to them, not their parents. The job of cart driver is another of these many small livelihoods that survive off the gold-digging manna. Here it is less the hope of fortune than the quest for independence and survival that motivates the teenagers to start working at an early age. School was quickly forgotten in the face of imperatives. Missa dropped out last year. Dramane had never been to school. Missa would like to go back to school, but not in his old class, with children who would now be much younger than him.

At 12 and 13 years old, Missa and Dramane are very conscious of the fact that they have to work to satisfy their needs. They are not unhappy with their situation; they have chosen to come here regularly to improve their lives.

Gold digging in Burkina Faso

Today, several West African countries such as Guinea, Mali and Burkina Faso are experiencing a proliferation of artisanal gold-mining sites, encouraged by the surge in market prices of gold following the global economic crisis. Gold remains a safe value for the global capitalist system. Gold-digging has been a historical activity in Burkina Faso for several centuries, but it has taken on a phenomenal dimension in recent years. In Burkina Faso, 1 in 18 people make a living from artisanal gold-digging. In 2017, the country’s National Assembly listed 1,000 gold-digging sites and estimated that 300,000 children worked there. Entire families live on site, others are lone “adventurers” of all ages, gold seekers in a 21st century where money still matters more than anything.

Compared to industrial mining, artisanal gold-digging is subject to much criticism with regard to the difficult working conditions, the anarchic occupation of space, and the impact of the activity on the environment… But there is no doubt that the populations benefit, in part, more from artisanal gold digging since, in a context of high unemployment, their earnings belong to them, unlike in industrial mining.

Leave a comment