Q&A With Director Zara Zerny, by Marta Bałaga

How did you choose your protagonists? Did you know them before?

In 2014, we made a short, Goodnight Birdie. Even though it was a fictional story, we used real residents from an elderly home. I remember talking to some women who were convinced they were going to die right after their husbands. When that didn’t happen, they felt they didn’t love them enough. As if death was some kind of declaration of love!

It stayed with me, and I wanted to search for more of these characters, I wanted to flip death around and make a love story from it. I thought it was so beautiful that this generation is allowed to wish to die for love, but only because they are old and have been together with them longer than apart. Then the pandemic hit, everything shut down and by the time we started to shoot, it felt like that generation was already gone. Which, in a way, gave this project a whole new layer. And I started to see the differences from this generation’s view on life compared to today. I tried to find protagonists who all had experienced loss of their life partner and looked at their different ways of coping with loss and how love stayed with them.

You are listening to people talking about partners who are no longer here. What made you interested in such absence?

How I remember my childhood is completely different from how my father would remember it. Memory is very much fiction, and it’s the same with these love stories. These people have all lost partners they shared their entire life with. And once you do, how do they stay with you? If that’s the case, in what ways? Of course, this film is about loss and about the past, but there is something uplifting about it. It talks about the present as well, because these memories are still alive within them, in their surroundings and through them. I hope they all have a feeling of their partner still being present, it is loving and hopeful, and it gives me something to believe in, when moving through life and trying to figure out what relationships are all about.

As someone notices in the film, people leave each other faster these days. Soon, we might not know these kinds of couples anymore.

I used to live in Canada before, with my parents and then they separated. I have never been introduced to a “coherent” kind of love. It was absent in my life – it always felt like a struggle. Then I came to Denmark, we moved in with my grandparents. And I was shocked how much their love filled the rooms and atmosphere. If I close my eyes, I still remember the smell of that house. Everything was so calm and now, when I look back, I think I was scared of that feeling. It was nice – I just had not experienced it. My grandfather died shortly afterwards and my grandma would talk about him constantly, and I could see her memories coming to life.

I call this film a portrait of a generation, because it’s true: Now, things are changing. Of course people stay together still, but statistically not as many as this generation. I am not saying that their way of relationships are better or worse, but I do believe we can listen more and reflect on what we want from life and love.

Another thing that has changed is that now, we talk about ourselves all the time. They were instructed to never air dirty laundry in public, I guess. Still, many share very intimate secrets with you.

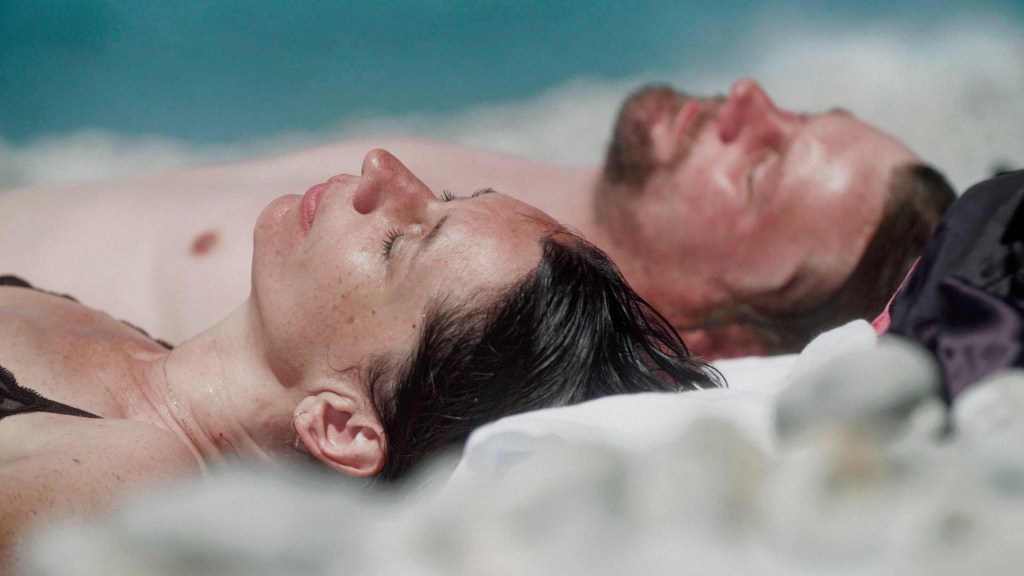

I have sometimes felt intimidated asking personal questions, especially to this generation about sex. I thought it would be difficult for them, but most were very honest. They told me much more than what’s in the film [laughter].

Even their own families don’t know some of these things. They trusted me and also, I think they were just shocked that someone actually wanted to know. Very often, we don’t ask our parents or grandparents about these things. We don’t ask about infidelity, for example, but we often wish we could. We decided that once they are no longer here, their family members will get these full interviews, with consent of the participants. We don’t always listen to older people, but I wanted to give them a voice. I wanted to listen and I learnt a lot. Talking to them was the best therapy I could hope for. They really make you go: “Why am I fighting with my husband? Why does life feel so complicated and hard?” When you are 80 none of it will matter anymore. It makes no sense!

These days, many filmmakers are afraid of the so-called “talking heads.” You prove there is still power in them, because they make it feel more intimate.

One could say it’s not the most interesting approach, but I find so much beauty in it. Especially in documentary. These people talk about their past, so we could try to recreate some of these events. But sometimes, instead of forcefully evoking a feeling, it’s enough to listen and observe.

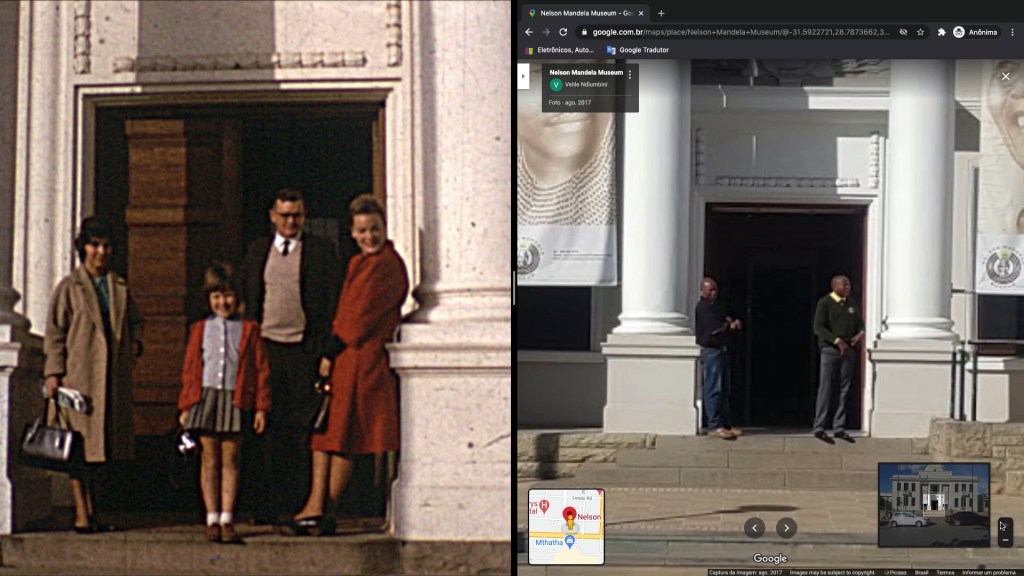

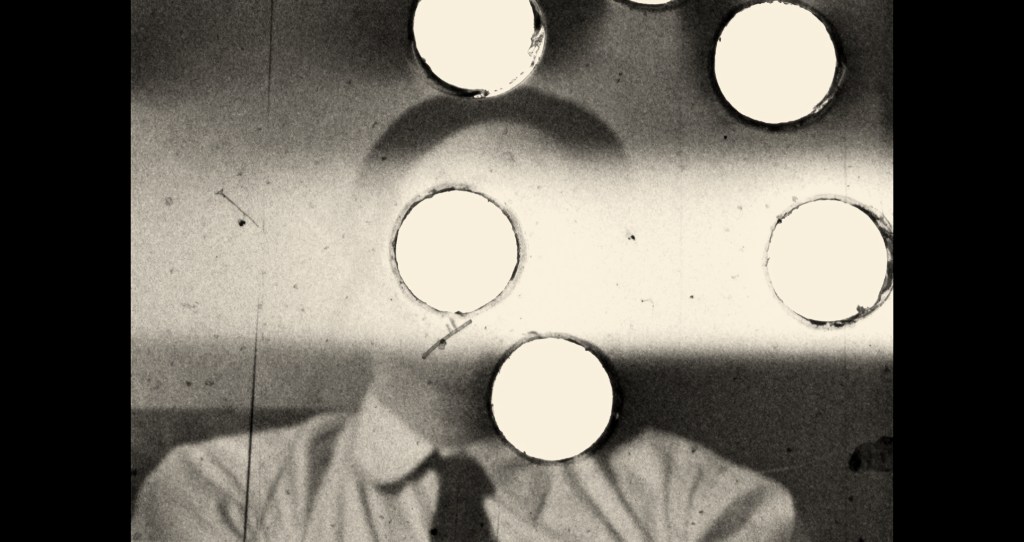

I wanted them to interact with old photos, however, or with videos. Also, referencing Erving Goffmanns, a sociologist, who worked with the terms front stage and back stage, I have always been interested in how I can “direct” a scene compared to where people are staged. By stageing interviews in different rooms in their homes, it changes the context. When they talk about love in the kitchen, it’s more factual. When we move to the bedroom, they close their eyes and suddenly, they look more vulnerable.

In filmmaking, just like in life, everything has to be so fast these days. Sometimes, we forget what cinema is all about: it’s about listening, watching and just experiencing something new. I hope we can still go back to these basics sometimes.

You mentioned this film made you think about your own family. Are you hoping others will too?

I wasn’t sure if it would be relevant to other people. As a filmmaker you never know if your subjects matter for others, and at first, I felt anxious and a bit scared. At the same time, I knew why I was interested in it. I knew that this intimacy actually taught me something. In the subtle way the protagonists describe intimacy is something I think we tend to forget while living our lives. We expect life to be great, eventful, exciting, but will that be what we look back on? My relationship has become better, I actually now look forward to getting old more, in a way, or maybe I have given it more thought. I have started making lists of what I want before that time comes. I have started writing small notes about sentences in my daily life with my kids. I am more scared I won’t remember the small things and the nuances in life.

Also I think this film brought me closer to my grandmother Inger, who is no longer here. I felt her presence in some of the people I talked to, and I have reflected a lot about her and my grandfather. She died eating a piece of cake, and I am grateful she got a quick peaceful death, but I mourned and wanted to talk to her again. I think I have talked to her in some way while making this film.

When we showed the film for the first time, people told me it made them want to go home and call their parents, others cried because it is so much about life. My own mother cried because she was sad nobody will talk about her like these people talk about their loved ones. I don’t believe that though because she has 9 grandchildren who will weep when she dies. (laughter)

We might not have marriages that last 60 years anymore, for better or worse, but there is something to learn here, because we do break up more easily. Maybe we lost something on the way?

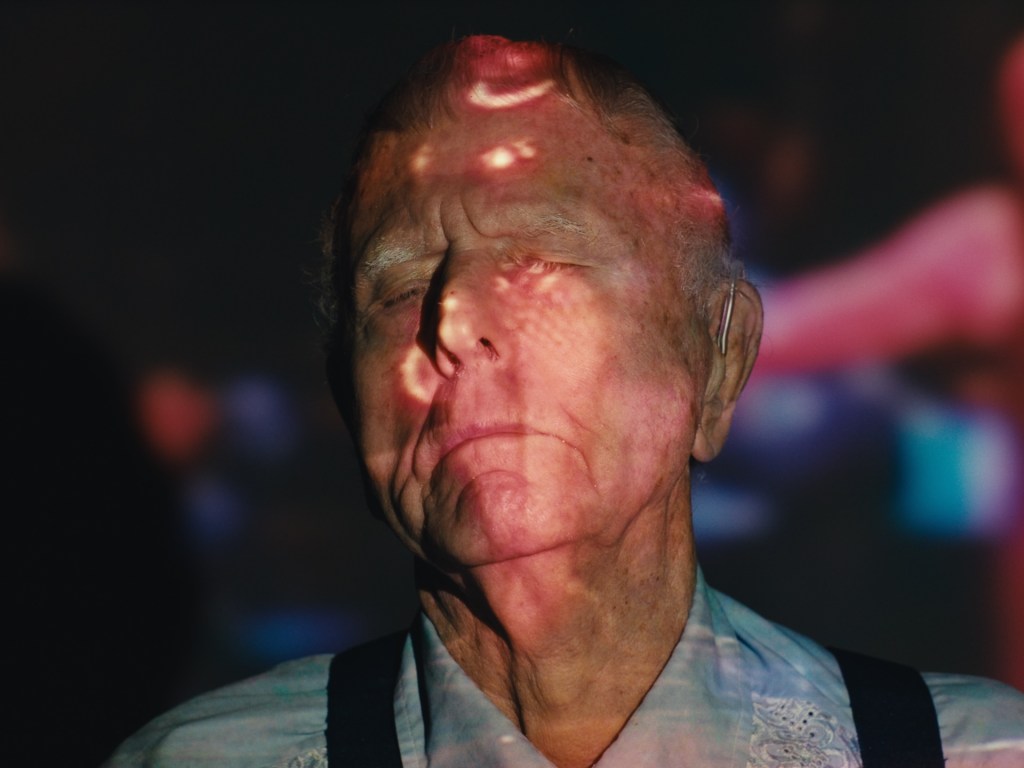

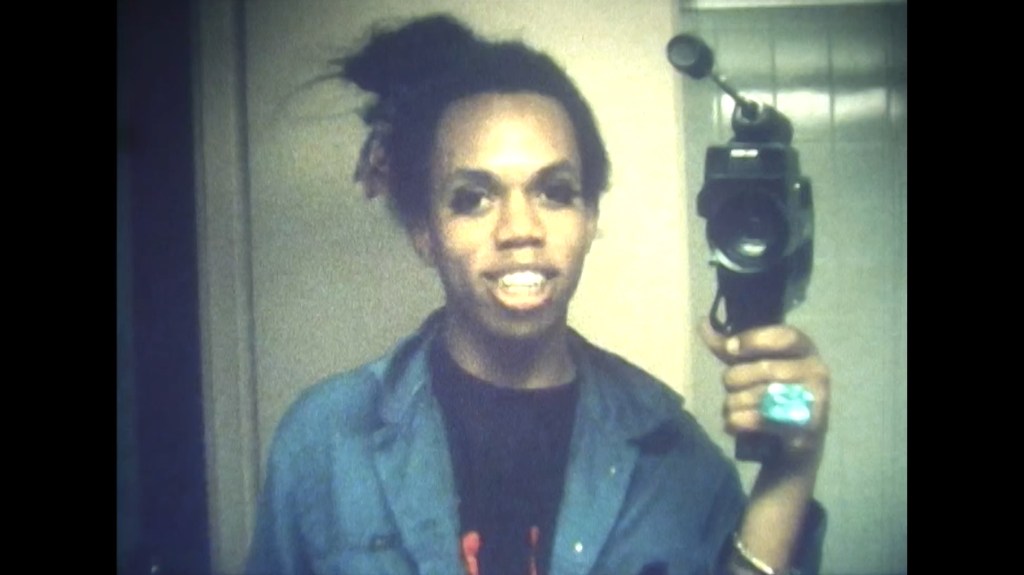

I just hope it will make us look differently at older people. They are so youthful inside. My husband asked: “Why would you make a film about them? It’s so sad. They are like ghosts in our society – we don’t want to fight them and we don’t want to sleep with them. They are transparent.” Well, that’s why. Because it’s not sad and it’s not scary. And when this film ends, maybe you will think about them differently, wondering what they can teach you, maybe you will notice the man on the bench in the park. That’s why I wanted to show their younger faces as well. So that we can go: “Wow! She was that woman!”

Is that why you come a bit closer by the end? To really look at them?

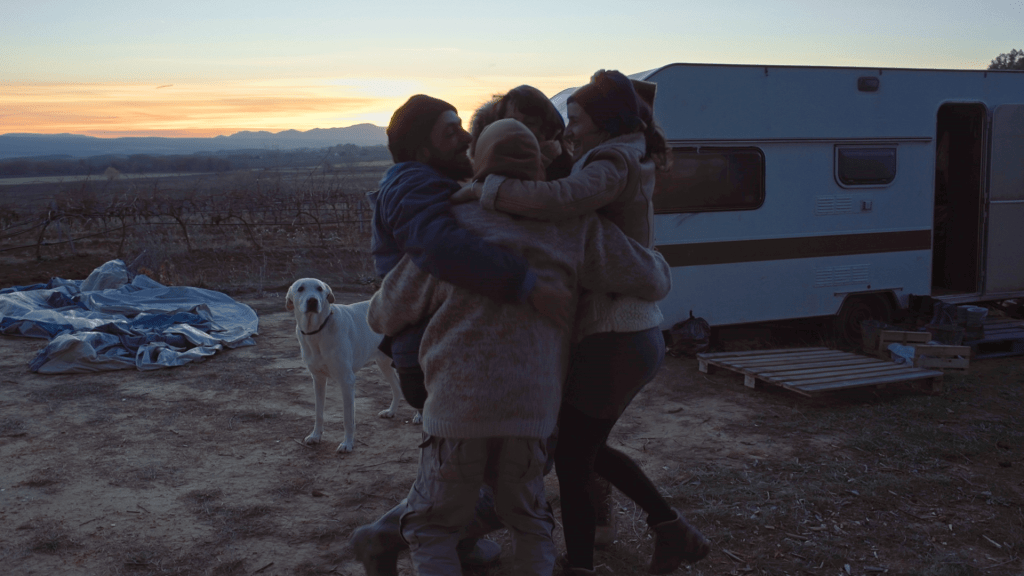

Yes, and for them to look at you. Actually, during that moment, they are watching their own life. I prepared this video for them, a compilation of some very important moments. I just wanted them to smile back. I cry when I see it now, because I can see life and that’s what I wanted. I never wanted it to be just about death. I really hope when people see the film, it will echo in them, and their transparency might become more strong and vibrant.

Leave a comment