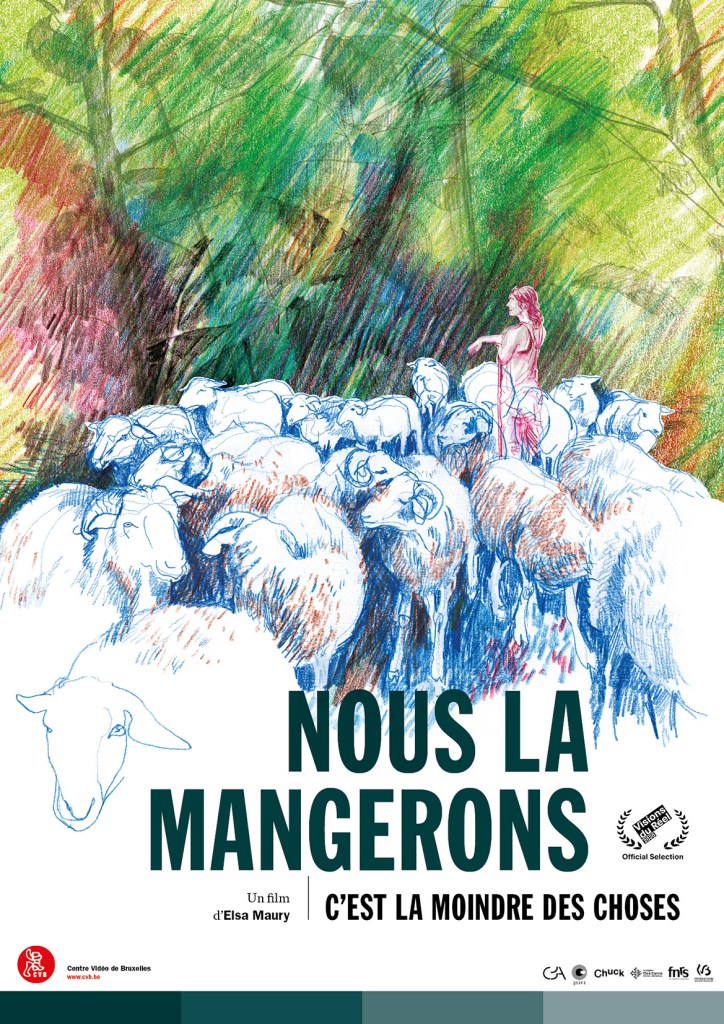

Elsa Maury – Director’s Statement

I wanted to make this film for personal, historical and cultural reasons. The project itself gravitates around the controversy surrounding the slaughter of livestock, which was brought back front and centre in the debate by the widespread diffusion of footage taken directly within slaughterhouses. It also placed the problem right on our plate: the consumption of animal flesh is neither harmless, nor innocent. I felt, however, that this matter raised the need for images and narratives formed from other perspectives.

A Point of View That Shows Solidarity

In this film, I take a curious and complicit look at a shepherd, Nathalie, and the way she practices her craft. I try to learn how we can kill and eat animals which we care for, which we have raised and looked after. I’m interested in the technical and emotional skills that allow her to “do things right”. Of course, this “right way” to do things varies between each farmer, each species, each territory. I chose to follow Nathalie and her flock in the Cévennes, because she’s a young shepherd and nothing feels obvious to her yet. She’s sensitive, endearing, and she’s deeply attached to her sheep.

“The ways of living and dying with which we feel in agreement – these one rather than these others – matters” – Donna Haraway

I would like to take this quote from Donna Haraway to clarify my own perspective. I opted to adopt a point of view that stands in solidarity with the shepherd and her sheep. I take the time to show the ways in which Nathalie works, physically, how she converses with the animals, and, ultimately, how she eats them.

When philosopher Donna Haraway talks about our solidarity with specific manners of living and dying, she immediately insists that the variations between these manners matter greatly. It took me several years of careful research to select my shepherd. I have absolute faith in my character, it is only with this in mind that I could explore the delicate question of death with her.

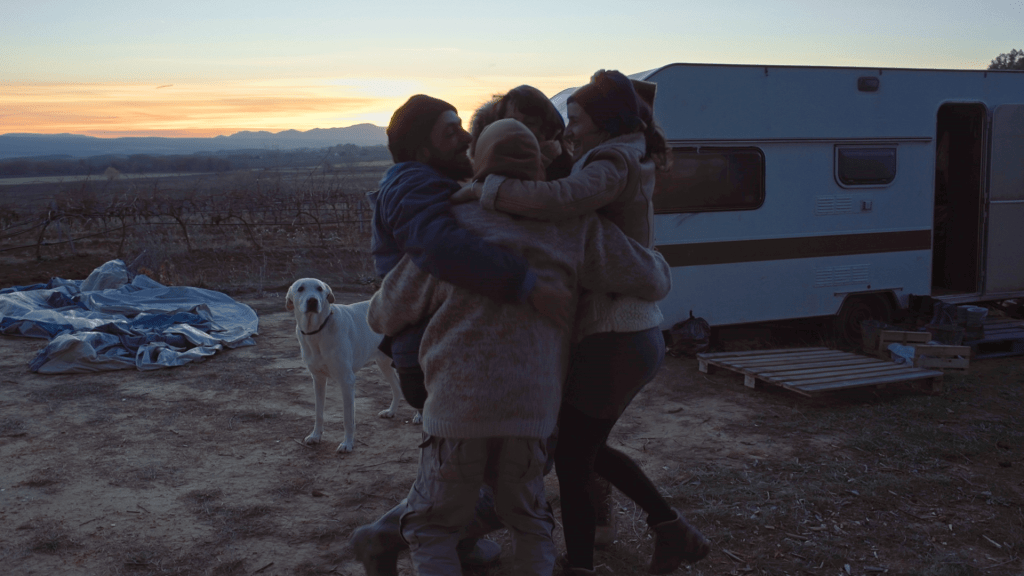

By choosing immersion, I made the choice to accompany her, to support her in her activities by my presence, by regularly lending a hand, or just by looking, rather by interrogating her. There is no dialectic confrontation in my film. The story it tells is not mine alone, but « ours » in some ways. It includes the texts Nathalie sent me as she kept me up to date with the events happening in her sheepfold. By caring about her animals, their filial relationships, their character, I entered the intimacy of the flock. The film tries to follow the experience of a singular and familiar character, who bravely questions how to kill animals that matter to her – whether it is done in a slaughterhouse or not.

Re-evaluate our relationships to animals and to the environment

The film attempts to show interdependent modes of existence between sheep, goats, birds of prey, parasites and humans, as various intricate ways of binding human and animal lives.

The way in which Nathalie has chosen to work – her “farming system” as they say – means that her life’s rhythm is entirely determined by the needs of her sheep, the seasons, their trust, the weather, the pastures in which they grow. This sheperd’s endeavour is absolutely original: she works without a sheepfold, without food supplements (grains, cereals, pulps, hay…).

The film delves into this co-dependance between Nathalie and the herd. She has to bring them to pasture every single day. That practice alone strongly differentiates their bond from the way the relationship between human and livestock is usually conceived since the 1950’s. It is no longer about providing them with enough nutrients in order to fatten them up and reduce them to immobility: it’s about living with them. Which means relying on their own will, the development of their skills in picking, selecting and eating the plants and trees in their natural environment. At Nathalie’s side, I witness her sheep becoming increasingly autonomous in their search for food, in the way they move around. Some of them become familiar, they trust the shepherd, who is there everyday with them. Without the walls of the sheepfold, the mobile paddocks always guarantee the imminent return of the shepherd, and the promise of a walk in the woods and the fields. The moving fences are a soft constraint for their bodies, a temporary artifact, over which they could jump at any time.

Nathalie’s work and her methods implies a different relationship to death. Life in the great outdoors – with all the comfort it can bring to the animals – also reinforces their immunitary systems and generates a selection between them based, among other dangers, on their resilience to illnesses and cold. This “rustic”, autonomous stock demands constant, day-to-day attention. And it asks the shepherd to accept the fact that death could be part of any workday.

Slaughter

For their death, too, Nathalie acts in solidarity with her sheep. She brings them herself to her truck, drives them to the slaughterhouse, leads them in and gives them “one last pat”. She is there with them at the end. She ensures the animal’s unconsciousness through a corneal test. She also works in the cutting room, packing up the meat.

Nathalie works at the slaughterhouse in order to care for her sheep until the very end. She also eats them entirely, cooking up their organ meats (lungs, liver, heart, brain…). For her, eating her animals means making life through death, by giving it meaning, and opening the possibility of renewal within the herd, through measured replacement dynamics. But this shepherd, with her small flock and intense, continued relationship with her beasts, does not provide a definitive answer to the question of the sheep’s death. And she does not want to offer a unifying theoretical discourse about it.

She learns to eviscerate, then to kill. This is both a technical and emotional challenge, which forbids any “innocent” posture. The film follows the animals and the events that lead her to enter this process.

Attachment and detachment

When I was a child, rabbit with mustard was one of my favourite dishes. However, its sour and creamy sweetness was inevitably the sign of a demise. According to a common custom in our countryside, my parents forbade us to give names to the animal we were raising to eat.

As if giving them a name made them inedible.

As if not giving the animal a name made it abstract (and thus necessarily edible)

This memory is revealing of a specific legacy, of a history of agricultural breeding and slaughtering. It’s in fact the scientification and hygienist practices of the twentieth century that brought about the abstraction of these animals in order to make their consumption easier. A strategy that is, in my mind, wholly unnecessary to the consumption of animal flesh. In my childhood memory, distance and detachment from the animals that we ate wasn’t obvious at all. Not playing with the goat’s kids, not naming rabbits, not getting attached, wasn’t simple. So I learned a different sort of attachment. I learned to mourn differently, and to appreciate the touch of sourness of an otherwise delicious meat.

It’s based on this history that I wish to offer this film that follows the entire process of turning animals into meat. By following the daily work, the gestures, it show different manners of being attached to animals, and of eating them, and invites the viewer to consider it as a form of acquired skill, that is absolutely not obvious. An ability, a know-how and a way of life that must be understood within their environment.

I make the gambit that, as a character, Nathalie can teach us to appreciate eating animals with names and histories. By following the path of a shepherd who wants to do things right, the spectator will understand that there is no peaceful resolution, no death that can be comfortable, obvious, rational, natural and without compromise. The film celebrates the perseverance of a shepherd that takes the risks to get to work while bearing these contradictions.

Leave a comment