Interview with director Guillaume Brac

How and why did you decide to shoot this film on the Cergy-Pontoise leisure base?

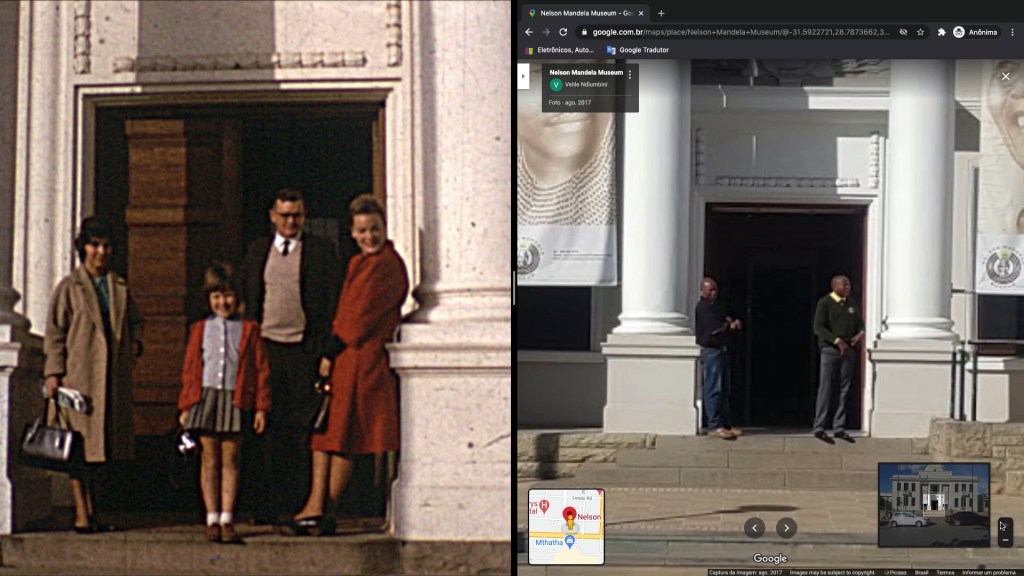

It’s a place that is part of my childhood and to which some very precise memories are still linked. We lived not far away and my parents took my brothers and sisters and I there from time to time. It was our weekend outing. Many years later, I discovered Boyfriends and Girlfriends by Eric Rohmer, and seeing a place that was a setting for my own life in a film that was important for me, stirred up really special emotions. Suddenly, this place took on a sort of mythical aura, and that made me want to go back there. The first time, it was a Sunday in September. The weather was really nice. There was joy and vitality, smoke coming up from the barbecues, that was sculpted by the sun’s rays. I was both fascinated and touched to see this mixed crowd, with all its cultural diversity, rubbing shoulders… it brought me back to some personal thoughts i’d been having on social segregation. I grew up in a privileged environment that I could have stayed cooped up in, cut off from a whole chunk of humanity. I believe that, without actually realising it, I started making films so that I could erase some of those borders. I was looking for some form of common denominator between all men. A great variety of people come to this place. Not all of them have had the same childhood, the same chances, far from it. But they are brought together by emotions and feelings that they all share, those that arise when it’s a summer day, or holiday time. During this time of the year, encounters between these different worlds become possible, whereas they are not during the remainder of the year. This is already the story that was told in part by A World Without Women.

There was also this idea of filming a place, a territory…

I’ve always needed to start with a place. That has been the starting point for each of my films. I would start by identifying a territory, then exploring it, meeting the people who lived there, building “emotional bridges” with them. That’s what captivates me the most. With the idea that these little worlds, which exist very much in their own right, end up telling the story of a much bigger world. until then i’d shot a lot in the provinces, and I felt a need to film the Paris suburbs. There was of course the question of my legitimacy in filming there. And this other question, that of the clichés that constantly have to be brushed off. My idea was to film the suburbs, whilst leaving them off camera.

Treasure Island is your second documentary after a medium- length film, Rest For The Braves. But your films already had a very particular relationship with reality, a desire to capture life, to allow it to circulate freely, including within the context of the relatively structured framework of the shooting of a fiction. How do you compare those two approaches?

My approach as regards fiction already very much bore the imprint of documentary work: starting off with a place and actors, or more precisely, people, because for the better part I filmed actors i knew very well and with whom there was already a certain familiarity that permeates the film. In Tonnerre or A World Without Women, there are also scenes that are almost chunks of documentary, sorts of holes in the fiction, where suddenly a non-professional actor talks about himself, offering a fragment of his existence to the camera. Those times in the shooting were particularly moving for me and confirmed a profound desire to capture reality. Yet, in my documentary work, I don’t fantasise about an untouched reality that’s filmed objectively. I look for meeting points, people i’m touched by and who will often bring about a sort of mirror effect that’s outside any difference in age or background. Treasure Island obviously talks about this place in a very subjective manner, by means of the people I wanted to film and keep when we edited. And with fiction as with documentaries, i’m very fond of things that happen by chance, that are unplanned. I even tend to make it so that things don’t go as planned. I can’t help myself and in fact it’s often very tiring, but i’m not interested in spending the day shooting exactly what was written down, editing… I always need to query what was organised, to shuffle things round, to upset the status quo, depending on what I’m feeling that day, and in that place. I think that with this film, I wanted to take a leap, really surprise myself, to leave an opening for just anything to crop up. it can really make your head spin and i had some great moments of solitude but from time to time, facing a person or situation that i could never have imagined or invented, i had moments of sudden realisation, that made me forget all that!

It’s the beauty of the unexpected… Yet there’s still very much a documentary style of writing that evolves progressively, particularly as you searched for locations. How did you approach that?

It’s a project i’d been working on for a few years, taking notes, regularly spending afternoons on the leisure base. From time to time, I’d see a film that brought to mind this feeling that I wanted to capture there. People on Sunday by Robert siodmak and Edgar George Ulmer, with all those people gathered together on the banks of a lake in the Berlin area, who for one summer day forget about work and daily life. With this heady feeling that for just a few hours, anything is possible… Black Peter by Milos Forman, with its bathing scenes that are both burlesque and sensual, on the city outskirts. Our Beloved Month of August by Miguel Gomes. Films by Rozier of course, which are important milestones in my love of cinema and that all tell the story of an interlude, a moment out of time when you get away from routine… And then in summer 2016 came July Tales, a diptych, that came about after a workshop with some young actors from the Conservatoire, and of which I chose to shoot the first part on this leisure base. With the idea in mind of roaming round the place, filming it a first time, tapping into it a little more, making it mine. Finally, in the spring of 2017, I started checking out locations on my own and during that time, i’d just observe, listen… I could spend an hour in the same place, catching snippets of conversation, accumulating impressions, sensations. i also met lots of the employees, young and less young ones, with whom a certain camaraderie grew and that was precious for me in the time that followed.

What was their reaction to your approach and how did the shoot itself go?

Above all, I was very lucky because the director of the leisure base turned out to be a great movie lover, a fan of Capra in particular! I showed him my previous films and he was very touched by their rapport to places and people. He immediately understood what I was looking for and trusted me, leaving me total freedom. Whilst I was scouting locations, I already established links with a number of employees. Most of them accepted that I film them. Some of them were a little wary, which is normal. I had to show a certain amount of pedagogy and explain that my approach had nothing of an inquiry or journalistic investigation. That I wasn’t looking for something to pick fault with or gossip about, but something both simple and profound, the human element, slices of life, moments that seem light-hearted but that can tell us a lot about people. The film shoot took place over two months, almost continuously. My producer, Nicolas Anthomé, who also put his trust in me in spite of the fact that very little of my project was in writing, and was therefore not very easy to finance, immediately got the hunch that we should film for as long as possible. He knew that was the only way I would find a method, that my mise en scène would be fine-tuned, and that the heart of the film would progressively unveil itself to me. There were four of us, Martin Rit on camera, Nicolas Joly dealing with sound, Fatima Kaci, a young cinema student from Paris 8 university, who played the role of both assistant producer and assistant director, and me. We lived on location. The film wasn’t written out in advance. I had simply set out a list of scenes I wanted to capture or try to provoke. Situations i’d observed during my scouting, such as people sneaking onto the beach without paying, others jumping off the bridge, or trying to pick up girls… Or they were stories I’d been told. But a lot of the sequences and characters were down to chance encounters, on bike rides round the leisure base. Such as Patrick, for example, the retired teacher. Or Joëlson and his little brother, Michael, who Fatima met one evening when they’d come onto the island alone. We had to juggle with a whole load of constraints, the weather, peak visiting time, the employees’ time off and above all this constant renewal, with this rather sad aspect of meeting people you’re never going to manage to see again. So as not to have any regrets, there were a lot of people we filmed straight away, the first time we met them.

The movement in the film really lets us feel the path you took: the exploration of this place that we enter into more and more deeply, that you roam around, make your own and that delivers itself to you, reveals itself. Finally, from this place come tales that are even more intense and intimate, as if space itself was unfolding…

We did a great deal of editing work with my editor Karen Benainous in order to give some sense to all these elements, and to bring out what really counted to my mind, what really touched me, to find a tone, a beat and above all to portray this hidden movement within the film, that carries the viewer with it, almost without him realising. It takes him from the abundance, and lightness of the beginning to something more melancholic, more existential. And effectively, Karen and I were pretty obsessed by the geography of the place, with this desire that the film should start off in the most obvious places, such as the bathing area, and that it should progressively move away from that central zone to the more hidden away outlying zones.

Like the one where the Afghan family is having a picnic?

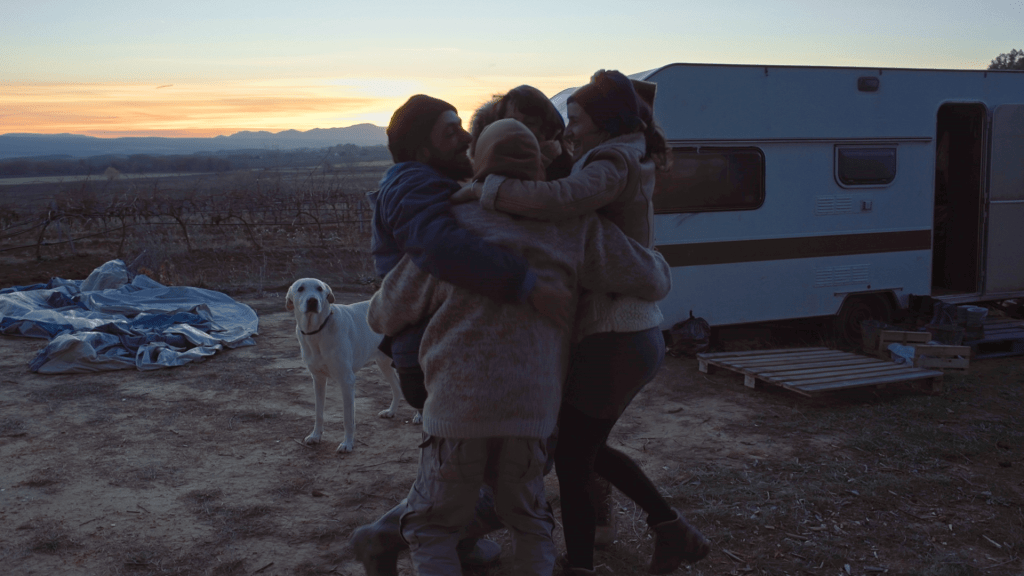

That encounter took place at the very start of our shoot, on the second day. They were just getting settled down in this delightful area, far from the crowds. It kind of made me think of A Day in the Country, with the water as a backdrop and the spots of shade. I really wanted to capture something straight away. I asked them if they didn’t mind me taking just a few shots of them, the preparations for the barbecue, the arrival of the rest of the family. And very generously, they accepted. At one point I heard the little boy asking “Dad, is it true that when you were 13 to 14 years old in Afghanistan and that you started to get hair on your face, you were sent off to war?”. The father nodded and then we caught each other’s eye. I wanted to say something, but i could tell that it wasn’t appropriate, that it wasn’t the right time and that they didn’t want to talk about that, they wanted to give the image of a happy family. Their tale, we only filmed it a month and a half later: I waited all summer for them to come back and when I saw them, and I was starting to better understand what the film would become, I explained to them that we’d filmed some great shots of them, that portrayed the joy of summer, of being together, but that I was missing the counterpoint of those images. They understood my approach and accepted to tell me about their difficult journey, that had brought them here. And they told the tale with so much simplicity, gentleness and humility.

There was something very political in what they said. As with the night watchman…

To start off with, my intention wasn’t really to capture a political statement, that came little by little, almost naturally. To start with, it was more the approach of the film itself that could have had something political about it, the fact of filming at the same height, with no distinction, people whose life stories were extremely different, who came from extremely diverse backgrounds, faced with the question of holidays, leisure, the summer, memories, seduction, solitude… universal emotions. I’m thinking in particular of that really simple sequence with the Filipino family playing dodgeball: seeing them in that context, where they have time to themselves, in one of their rare moments of relaxation, freedom, with the children’s incredible, communicative joy. It was really touching. What’s dreadful about daily life is that we all cross the paths of an infinite number of destinies of which we know nothing at all. Our lifestyles mean that we’re not curious or generous enough, we don’t take the time, or have the desire to get to know others. suddenly, with this shoot, an infinite number of encounters became possible.

We also meet people such as Patrick or Jérémy for whom the island represents a land of freedom.

Yes these two characters have a really strong link to this place, but even more to youthfulness. Past youthfulness for Patrick, that comes through when he talks about his school outings with his students and above all his disconcerting encounter with the young girl of 20. Youthfulness that’s being lived – and that’s coming to an end – with Jérémy, the blond Adonis from the pedalo rental. he’s a character who, almost alone, illustrates the sunny side of the film, whose vitality and thirst for encounters and experiences permeate the whole film. He’s much more than a charmer. He’s extremely pure and his relationship to other people and to life itself is disconcerting in its simplicity and spontaneity. There’s something of Peter Pan about him, with his fear of growing up and leaving the world of childhood behind. This island really is his territory. As it is the film’s territory. I would almost say that his character portrays the film and even my films on the whole, this articulation between lightheartedness, comedy, his rapport to games of seduction, and something a little more painful, more melancholic, that only emerges little by little.

Effectively, if the treasures that this island hides are these encounters, and through them, this human community that takes shape, the film is also tinted with a form of reminiscence of childhood, the most precious of possessions, alternating between absolute vitality and melancholy…

For very personal reasons, my relationship to the cinema is very closely linked to the idea of keeping track, going against disappearance, forgetting, death. With the accompanying obsessive need to grasp slices of life, moments of joy and insouciance, that we know are all ephemeral. That’s what the melancholy in the film hangs on, this idea that things inevitably come to an end, that youth doesn’t last eternally, that one summer day is almost over just as it’s barely started. It’s an adult’s feeling. Children, luckily, aren’t aware of it and that’s what makes their vitality even more precious. During the whole shoot, I was fascinated by the children, to an extent where often Martin and Nicolas would tell me to stop filming them, that we had enough – and effectively we cut out a lot during the various editing sessions – but I just never got tired of watching them! There were emotional reasons for that, but also purely cinematographic reasons: i’ve always been fascinated by the way life comes to animate or fill up a cinema frame. And the quintessence of that is children on a beach with this abundance, this wealth of simultaneous actions, that mean you could look back at a frame a hundred times and notice new details every time.

Could you tell me a little more about the way you film real life?

There’s something I noticed when we were editing: we did a lot of shots that I would call “Light shots”, that were quite primitive, static, large, and life comes into them and unfolds. Like with the shot of the bridge at the beginning, with the teenagers who are jumping and the children from the leisure centres, who clap and shout joyfully. With Yongjin Jeong’s very lively and slightly naïve music, it almost makes me think of a silent movie scene. During our shoot, I was obsessed with the question of the scale of the frames. I constantly asked Martin Rit to do wide angle shots, shots that showed several people, several actions. Finally, there are practically no close ups in the film. And there’s a large majority of static shots, giving the viewer a freedom in the way of viewing things, that I find very important. This way of shooting was an extra difficulty. In such an eventful documentary context, it wasn’t always easy to put down the camera, to compose a shot. But I could feel that it was what i wanted, to frame life… And there was this idea that the film’s main characters are this place and this season, and what’s wonderful is to see how each one becomes part of the space and that particular moment.

Yongjin Jeong’s music is both joyful and melancholic. There’s also something very childlike about it. How did you come to work with him?

For me, the work on music never just happens. Each time, it’s the fruit of a lengthy trial and error, a long thought process, to find the music the film calls for. For Treasure Island, I vaguely felt that we needed something very simple – seemingly so, at least, because doing something simple is often what’s most complicated – like a little jingle, that comes stubbornly back, etching itself on the viewer’s mind. In my mind, the music had to be the link between the characters, whilst telling the tale of passing time, as we go from day to night, the death of one summer day and the birth of another. I also really liked the idea of working with a foreign composer, as if it were a way of remaining faithful to the universal dimension of the place. I had the impression too that my film, in it’s form as well as in its sensitivity, had a sort of discreet link to Asian cinema. That’s what lead me to Yongjin Jeong, whose work I adored in Hong Sangsoo’s films. He has a real feeling for melody. What’s very touching is that when Yongjin discovered the film, without subtitles, so without understanding what was being said, he still managed to find in it a lot of things that took him back to his own childhood or summertime melancholy. That really reassured me and I think that his music brings real universal colour to the film.

The film starts with a veritable embarkation and finishes with the “onslaught” of a hill, elements that are quite evocative of Stevenson with this idea that is behind every story, that at a child’s level, everything is adventure and all is spectacular. It’s a film that has a lot to say about initiation, learning, and bypassing prohibition.

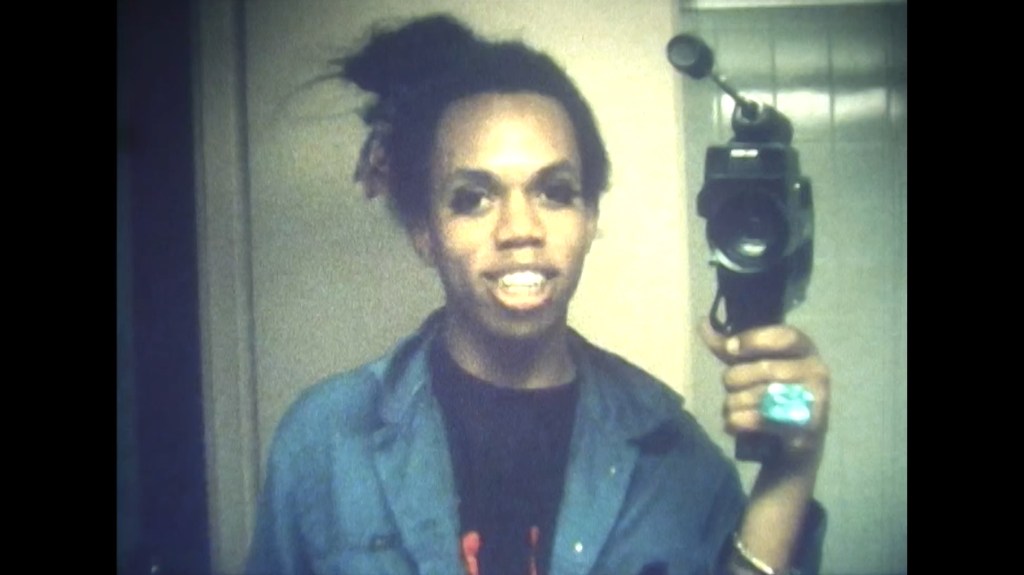

The film’s title, which is obviously borrowed from Stevenson, was obvious for me for several reasons. Treasure Island, the book, is effectively a quest, a tale of learning, and the story of a mutiny, the challenging of authority. It was quite unsettling for me, when we were half way through editing, to note that there were hidden similarities between all the accounts, all the characters that the film “accepted to keep”. The relationship to childhood of course, we said that. But also to freedom, authority, insubordination, transgression, which are omnipresent even in what Bayo, the night watchman has to say, his story that tells of his cry of revolt, his freedom of speech and insolence that cost him so much. Progressively, almost subconsciously, this rapport to freedom and rules became the core element of the film. To start with, I had considered this place as a place where freedom reigned. But I very quickly realised that even there, there were a multitude of things that were forbidden, and rules, and that this leisure base was in fact modelled on our society. When we started shooting, I effectively had a rather teenage rapport to this idea of rules, which naturally pushed me to be on the side of the scammers, and put me a little at odds with the base’s management – who were luckily very kind and considerate! What should be a place of freedom isn’t, but could things be any different? Yet, it’s was not forbidden to laugh about it. There’s something quite amusing and a bit absurd in this little game of cat and mouse played out day by day by the youngsters and security guards – who often did the same naughty tricks a few years before – around the strategic spots represented by the beach, where you have to pay to go in, and the bridge…

That’s why i’m particularly fond of the scene where Michael and Joëlson stop in front of the big sign showing all the things that are forbidden, and list them off one by one, with their childish innocence, making fun of them at the same time, without realising.

You regularly come back to the director and his deputy…

In this place that I film a little like a great big school ground – I often talked about Zéro de Conduite to my editor, Karen, a figure of authority was necessary, like a headmaster, who does his best to maintain a semblance of order. Yet, I find that there’s something very likeable about them, and quite comical too. In any case, I can’t film people for whom I have no sympathy. For me, Nicolas and Fabien are a little like the “summer guest speakers”, the only ones who stay cooped up in their offices, when the whole of the film takes place in the open air. They’re also one of the numerous duos we come back to throughout the film.

You mentioned games, there’s another interesting game in your film. It’s the one that develops between you and the people you film, between reality and what looks like the beginnings of fiction… Could you tell us about the “pact” you make with your characters?

Effectively in the film there are several documentary styles that come together, between capturing scenes and certain situations that i can organise after having been present without the. Quite ironically, i realised that i often got many more things spot on by provoking certain situations, rather than just hoping a little naively, with overly inflexible beliefs, that things would just happen on their own, as if by miracle, on camera. it’s often when we had a balanced pact, clear and fun, with the people I was filming that we got to shoot the most beautiful scenes. Certain situations, the scenes with flirtation in particular, are bordering on fiction, because I provoked them. But very quickly, the documentary aspect came racing back and something absolutely real would take place in front of the camera, with words, gestures, the way people looked at each other and even feelings. When Reda watches young Emma leave after she’s given him her snap, there’s love in his eyes and in his words. he’s really fallen in love with here. he really wants to have children with her!

There’s the famous Flyboard scene! When you talk about reality that comes racing back, there’s also the scene with the jump from the pylons, a pure slice of life, strong sensations, existence.

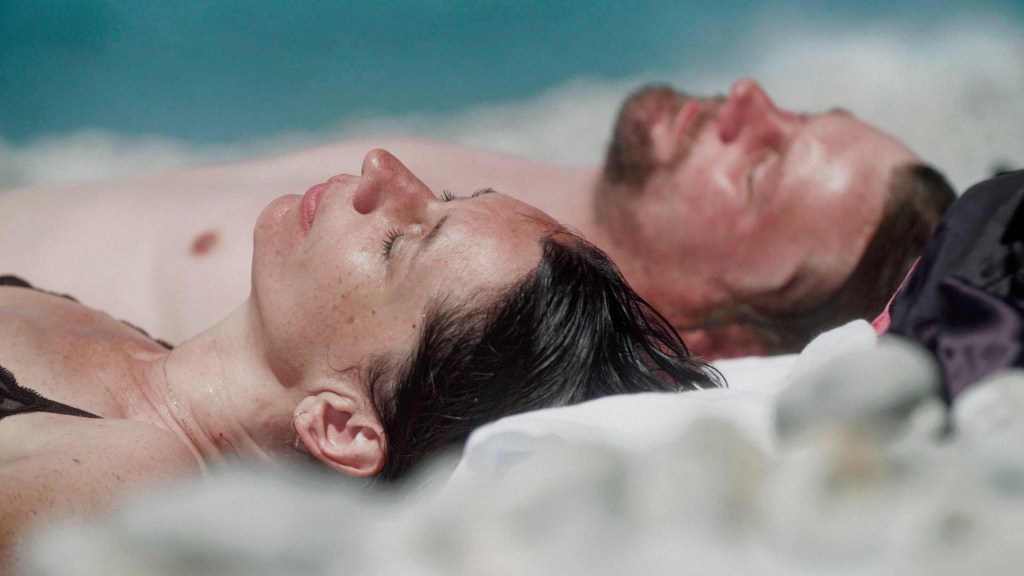

This is yet again a situation that I brought about to start off with. But both Jérémy and lisa started believing in it and something really did happen. I don’t mean outside the film, obviously that’s none of my business, but on camera. I found the moment when they were up on the pylon and jumped very unsettling, this sudden inrush of the unexpected in the midst of a summer day, that totally blew apart the ordinary course of things. lisa came for a ride on a pedalo with her friend, and finds herself taking a 10-metre high jump for the first time in her life, hand in hand with a handsome young man. In a way, it’s Jérémy who wrote and staged this situation, it was his idea, his ritual, his playing field. Once they’d got past their first meeting, I didn’t intervene. A moment like that practically resumes on its very own the precious and ephemeral magic of the summer.

Interview by par Elsa Charbit

Leave a comment