Simon Chambers – Personal Notes from the Director

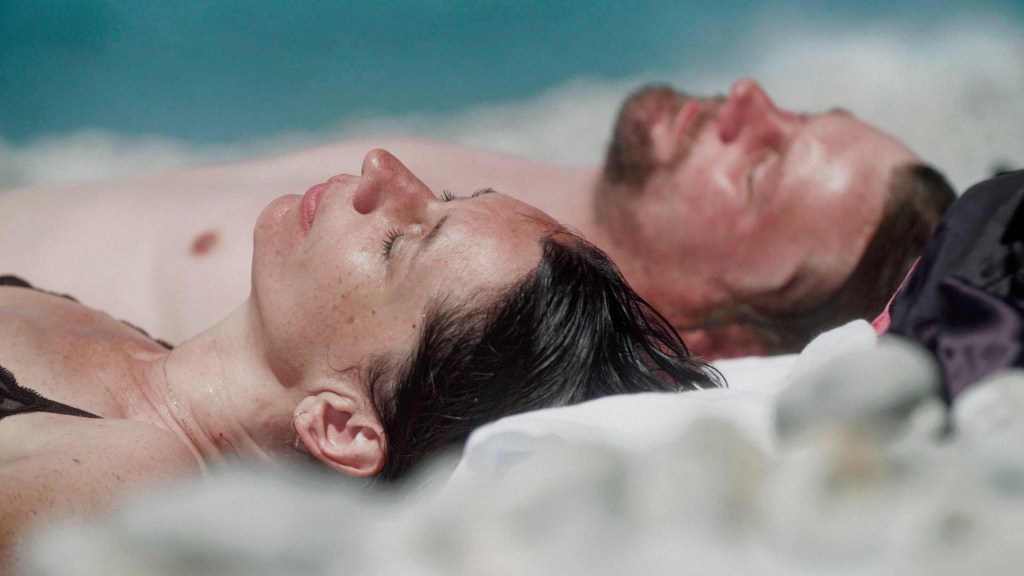

I never wanted to look after my Uncle David and I never intended to make this film. It was David, as an 85 year old actor, who insisted on me bringing my camera along every time I came to his house. I soon realised that we got on much better when the camera was around. He was always in a better mood because like all actors he loved performing. and it gave us something to fill the hours together.

It wasn’t until quite a few years after I had been looking after David that I realised how much, as a society, we need to talk more about the experience of looking after older family members. It is undervalued work. You can never predict what is going to happen next – when they will fall over, when they will get ill or when they will lose their memory. In David’s case this was extreme: he was being groomed, paying tens of thousands of pounds to a sexy heterosexual guy he fancied. Then he burnt the house down to the ground because of the dangerous electric heaters that I tried to stop him from buying.

All this happened because David wanted to remain independent, and to continue to make all the decisions about his own life. How much do you intervene in the bad decisions of loved ones, and how do you know that your own decisions are any better? I discovered first-hand the peculiar mix of anger, love, frustration, fatigue, loneliness, and occasional joy that other carers have said they also feel. Then there was the dreaded care-home that, in the end, concerned for his safety, I made him go into, against his will.

I have always chosen to film as intimately as I can, so that the audience come on an emotional journey with me. If I am going to reveal the intimacies of someone else’s life then I feel that it is only fair for me to reveal myself on screen too. I avoid interviews or “talking- heads” because I want this to be a film where the audience have the experience by seeing it unravel in front of them rather than simply learning information about the subject matter. My kind of documentary making is about understanding and empathy rather than just information and knowing.

I want the audience to see a deeply personal and intimate drama unfold in front of them. At times David, the actor, spontaneously launches into his beloved King Lear speeches. I became aware one day of the uncanny parallels between David’s life and that of Shakespeare’s king, who is going mad and wants to give his kingdom away to his daughters. It was strange how, when David was forgetting so much, such as how to operate the television, or who his doctor was, he could reel-off whole tracts of Shakespeare from memory. He said with regret that he had never had a chance to play King Lear, and so I thought that this film we made together was the closest I would get to helping him achieve that goal.

Before I started looking after David I think I had forgotten how to have fun and remain playful in my life. Editing the film was like therapy for me because the editor Claire Ferguson kept asking me how I felt as she tried to capture the emotions from the raw material.

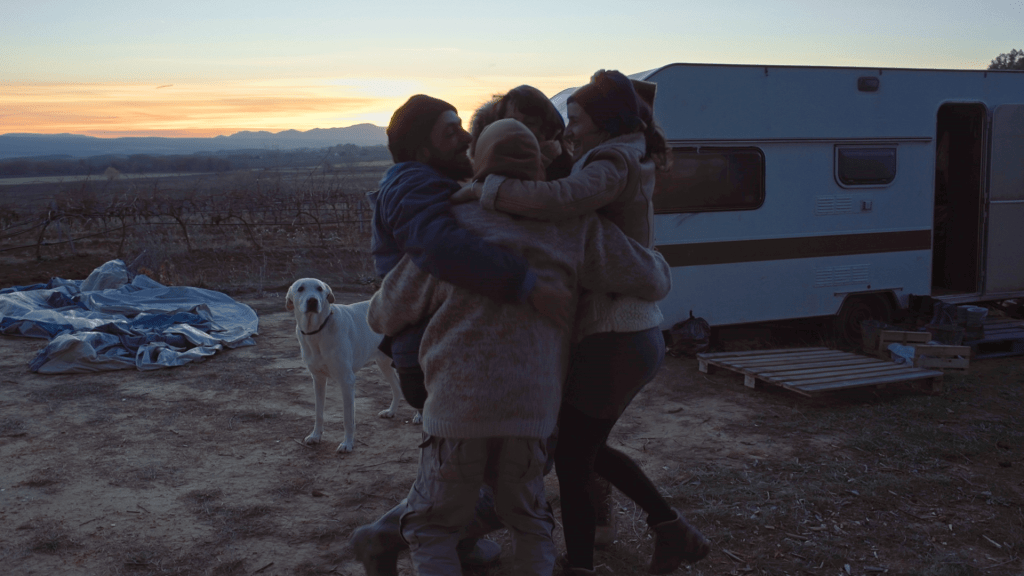

Apart from seeing the trauma that went along with all the responsibility of looking after him, and wondering if I was doing the right thing, I started to see the positivity, playfulness and wonder with which David saw the world and his life. Even in the face of adversity, such as his house being burnt to the ground, he would see the positive: “I’m liberated from my possessions!” It was a reminder to me to start being like this again in my life. When you know you are close to death it puts all our other worries in to perspective. I went from resenting to realising what a privilege it can be to care for an older person, and how much it is undervalued in society.

Even while he was dying, David had an enormous passion for life. If it is an actor’s job to reflect our lives, our hopes, fears, and dreams back at us, then David does a brilliant job of talking us through his own death as it happens, and in doing so shows us that it need not be frightening. It is something that we will all go through at some point, and I believe that much of the fear of death comes from our lack of exposure to it. At no other point in history has death been so hidden away, and in movies it is usually represented as either violent (in action or war films) or the passive flop of a head. The reality for most people is that it is a process which goes on for days, months or even years. I was determined to give David ‘a good death’ and to reassure the audience that such a thing is possible.

I found that, after the film, carers really want to come together to talk about their own, often traumatic, experiences – maybe for the first time.

It wasn’t until quite a few years after I had been looking after David that I realised how much, as a society, we need to talk more about the experience of looking after older family members. It is undervalued work, carried out mostly by women, and mostly by people of colour. If you are a family carer then you are twice as likely to have mental health issues than if you don’t do this work. It is for that reason that I dedicate this film to all the unacknowledged, unpaid family care workers out there in the hope that their work will become more valued and more visible.

Leave a comment