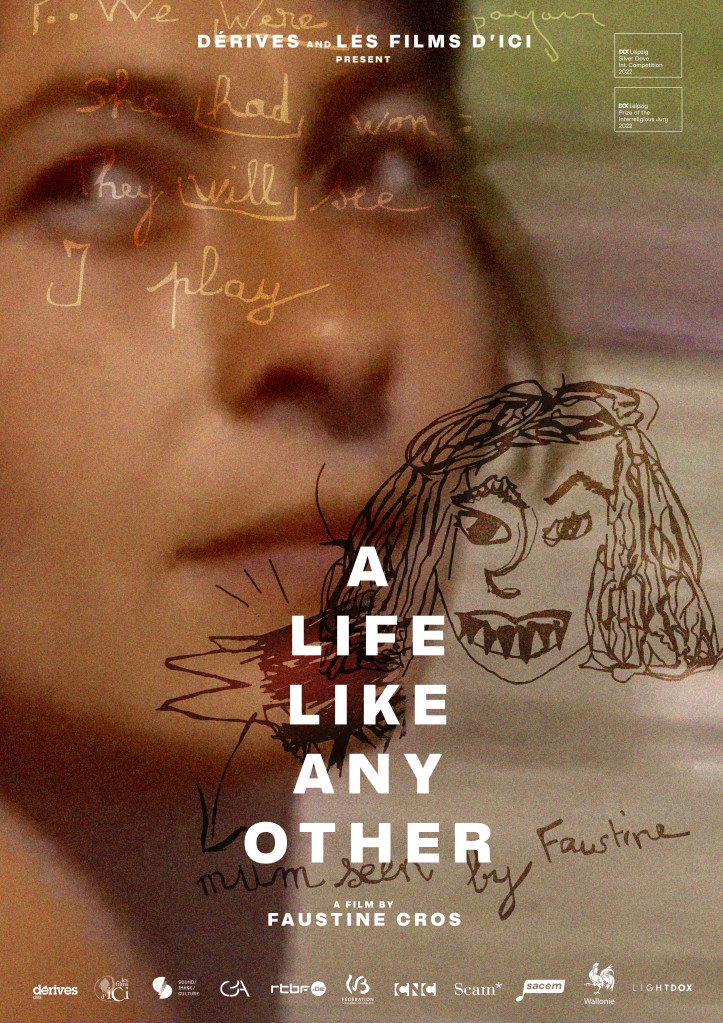

Interview with director Faustine Cros – by Catherine Lemaire

What made you reclaim these images and reinterpret them?

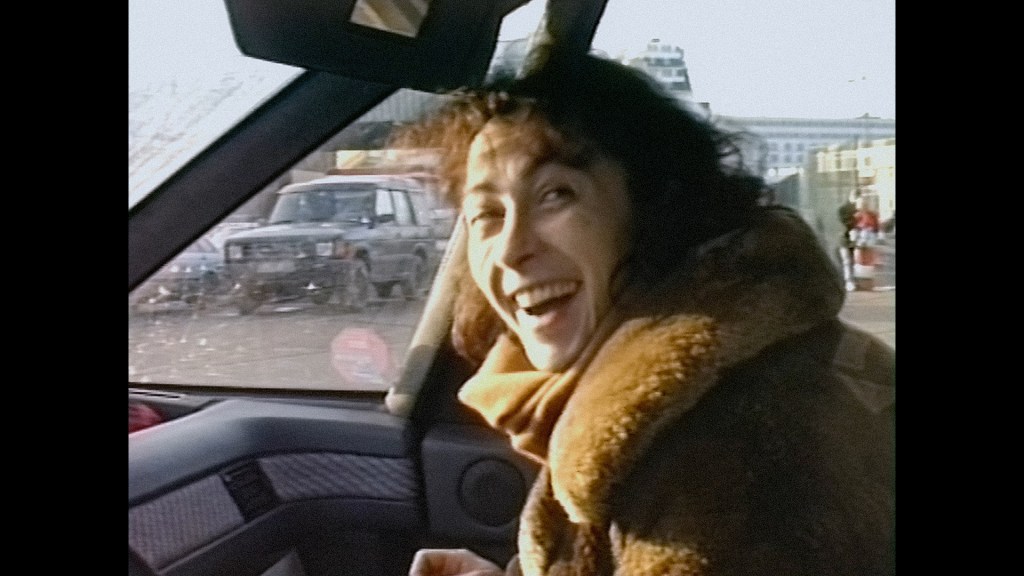

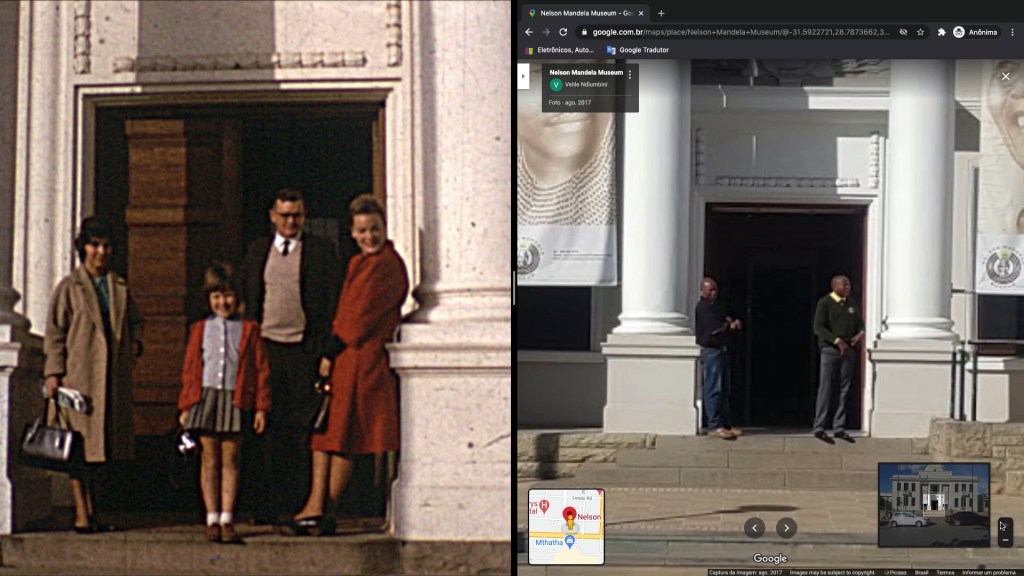

For me and my family, these images were part of life, a natural extension of things, even though partially staged. So the images my father filmed have always been there alongside me, I grew up with them, they helped me to become who I am. There wasn’t really any question that they represented reality.

I started to wonder about them when my mother went through a very difficult, painful period. I wanted to understand how she had reached that point. I intuitively felt that if I re-watched images from my childhood, they would perhaps tell me something other than what I had hitherto seen, that I would discover in them a new, darker facet of our family.

And indeed, as I rewatched them, putting them one after another, in chronological order, I got a real shock. My mother’s whole journey is there to see: the end of her pregnancy, my birth, her initial fulfilment as a mother, and then her slow descent into hell.

It was pretty challenging to realize that this part too had been filmed. My relationship to these images changed: I tried to see what my father had not seen, even though he was always the one behind the camera.

Precisely, one of the things we see and which strikes us today is the relationship to household tasks, to the caring of the children… The gender issues, which are not openly broached in the original archive images, become one of the major topics of the film. How do you approach these issues in the images that you film 30 years later?

I film real situations, my parents’ daily lives, which reveal a man and a woman who have consistently stuck to their roles, already boxed in long before I started filming.

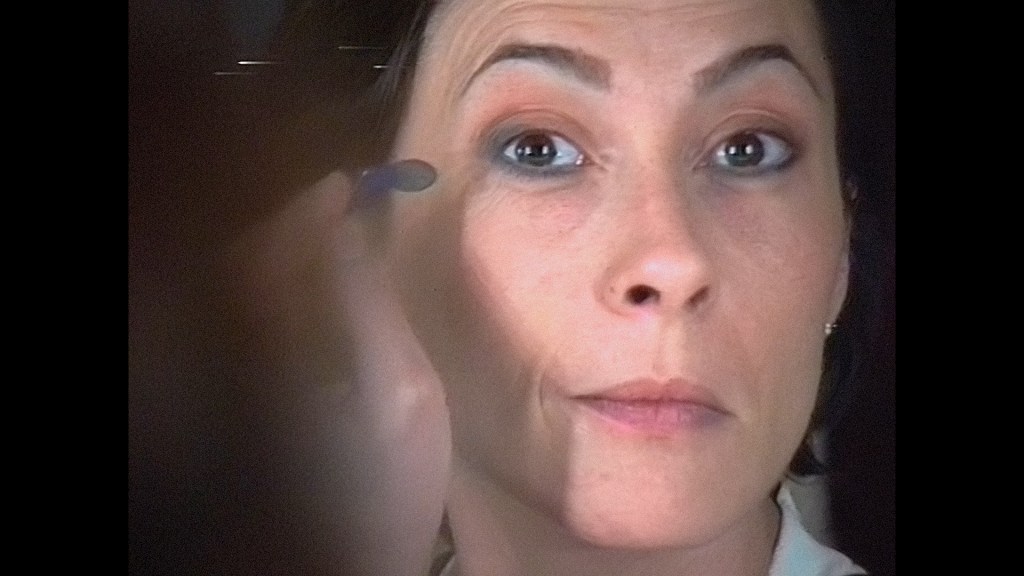

With my own images, I try to take a tender, sometimes amused look at their self-imposed confinement. I show my mother as a woman slumped dejectedly on her couch, who wanders aimlessly between the living room table and the ashtray, whose life seems to have come to a halt. And my father comes over as a hyperactive, compulsive handyman, who escapes through constant busyness.

I wanted to put the two types of images (archives and the footage I film recently) end to end to highlight that there is politics in private life: Why was it natural for my mother to abandon her career and bear the whole burden of household chores? And how did this unequal distribution of tasks become the norm over time? In the archive images, it’s quite striking to see that she doesn’t immediately realize that her decision to take on the responsibility for the children and household, initially a temporary one, turns out to be impossible to back out of.

I also wanted to show the other factor, the sexism of that era. I bring it to light when she tells anecdotes about her solitude, and about the way she was stonewalled by the doctors, who did not take her suffering seriously at all.

In the face of all this (the archive images, my images, their testimony) I became aware of how heavy the roles that we impose upon ourselves are, and of the injustices within my own family and more broadly, society as a whole. By picking up my own camera, I simply revealed this state of affairs. Society changes, of course, but these patterns remain. The impact they have is very real, as shown by the damage done to my mother over her lifetime.

There are many contrasts between your images and the archive images, not only in terms of “staging”, but also in terms of framing. How did these differences arise and why?

My father was also a filmmaker and collected images knowing that they would become memories. He was in the here and now, camera on his shoulder, committed to sublimating our everyday life. And he applied his expertise at home: he would sometimes do several takes, he was bossy, and was an adept of the notion that the person filming should never intervene, as if it were a sacred and tacit law of “traditional” documentary filmmaking. But this is also what engenders the ambiguity of his images, part family film, part real staging. I wondered if he had, consciously or not, missed the more problematic, challenging moments. Did he not see or not want to see them? Asking myself this question made me look for my own answers in the way that I filmed. I chose to adapt myself to daily life, to let reality be seen, in order to be as authentic as possible. I sometimes set up the camera and let it run for half an hour, to see how bridges could be created with the past, if any vestiges, ghosts almost, could be brought forth that would put the archives into perspective. But my camera also showed that their life had not changed.

In addition, my approach to intimacy was totally different: I wanted to find the right distance.

I feel it is crucial to remain demure, even when one is showing something very intimate. One of my responses to this was to use fixed shots, which necessarily creates a certain distance in the point of view.

You come from a family of filmmakers and you make a film about your family. Is this film your way of finding your place as a filmmaker?

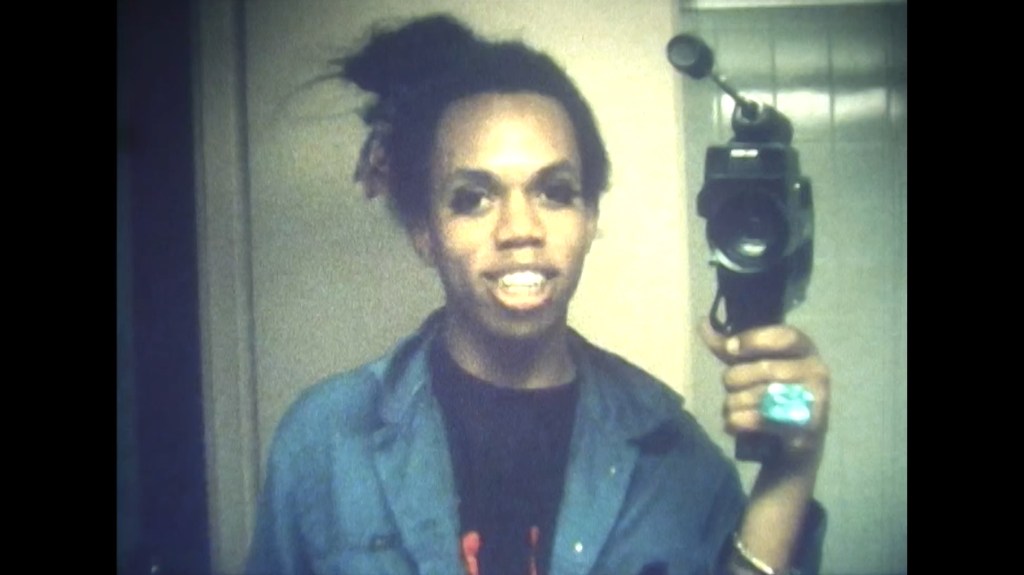

Yes, it was a way of finding a place for myself following in the footsteps of my father (and my grandfather, who was a director), even as I filmed myself and my mother! To take up the camera and gradually figure out my own place is an underlying thread that builds throughout the film. I carefully dosed my presence so that the viewer initially thinks that I am acting “just like my father”. Then the viewer realises that I am gradually deconstructing, setting off in a new direction with my own point of view.

I conceived my images as a way of reinventing a space for myself and my mother, to take back control of our image, our story and make our peace with the camera. By thus regaining control (my mother as much as I), I found my place as a filmmaker and broke free.

One senses that great care was taken in the narration, particularly that achieved through editing. How did you go about this, and, especially, how did you establish a dialogue between the archives and the “contemporary” images?

I started by viewing all the archive material, trying to see them in new light taking into account my mother’s suicide attempt. But I did not want to “force” the images, make them say something different to correspond to an idea that I already had in my head. That’s why I chose to show them in chronological order.

I had a very clear idea of the stages that my mother had gone through and those stages act as milestones in the film. Between those stages, I went back and forth with the present.

First comes the idea of a happy, fun-loving family, a little nutty, but full of love, then a passage in the present in the form of a question: “How did my mother reach a point where she attempted suicide?” That creates the starting point of my approach and a marked rupture between the archival and present-day images.

By then returning to the archive images, I show what leads my mother to her domestic entrapment. Returning to the present again, I wanted to go further than the simple observation that she was depressed and so made arrangements to get her out of the house and help her overcome the boredom and emptiness she feels.

At this point, viewers see, I hope, the mother and daughter starting to reconnect.

In a third return to the archives, I show the limitations of this situation. Firstly, I expose the complexity of a situation in which my mother had been so happy to have children while at the same time realising the alienation this brought upon her.

Then there was the impact that had on us, her children and husband. This becomes very visible when my father steps it up a level and decides to “really” make a film about his family, which results in this strange scene where my mother explodes and blurts out her disaffection to the camera.

When she “blows her fuse”, we have reached the sore spot. She is lucid and knows full well that the “monster” she would have liked to confront is not necessarily her husband but society as a whole, the patriarchy. Here we see the precise point when private life intersects with politics. I wanted to examine the family at that highly complex place, where love and violence blend together.

Your parents seem to be happy to cooperate, but there are nevertheless moments of resistance. What was their relationship with your camera?

My father was honored to be in front of the camera, it pleased him. Though it did not bother him to be filmed, he was very careful with his words because he knows what image he is projecting of himself. So it was difficult to get to the bottom of things.

I therefore decided to film him in situ. He is always busy doing or repairing something, and I thought he would perhaps lower his guard, or at least that his denial would show through in spite of himself.

With him, I wanted to respect his life path, the fact that in his time questions of mental health and patriarchy were not posed in the same terms as they are today. I wanted to bring forth the touching aspect of his denial.

With my mother, I first had to deconstruct or get her to unlearn the relationship she had with the camera, which dated back to my father’s filming, where she had to perform well, rehearse, etc.

So I worked hard to get her not to do things for the camera but for me. And gradually she accepted the camera and my role, which was more interactive, more involved. I kept the moments where she resisted, for example, when she grumbles that I only film her when she’s smoking. It was very important to accept the fact that there is something unpleasant about having to play the game, that one never knows how my mother will react to being filmed again. That is part of the “reconciliation” process with the camera. Here, she was not at the service of a shoot, the shoot followed her. And she could refuse at any point.

Were you parents enthusiastic about your project? Was it easy to convince them to reinterpret their own lives?

Yes, it was! As they are both in cinema, it was like an extension of their professional life, but in private. And when I started to ask my questions about the relationship between men and women, I was impressed by their sincerity, by their will not to dodge the bad aspects, the mistakes, the clumsiness. I was deeply moved by their generosity.

In addition, it taught them something about themselves. It did my mother good, I think, that I brought up the resentment she felt in relation to many things.

Gradually, my father started cooking, thinking, until, lo and behold, he made a hyper feminist film!

Did you have any specific approach to emotions? Few are expressed in the film and the voiceover is somewhat neutral.

I do not feel an absence of emotion in my parents, but it’s true that it pleased me to play on a form of modesty. The emotion is felt despite them, despite me too, through what escapes us, our clumsiness, little slip-ups in language, etc. I feel this is more interesting, it creates a cinematographic space that moves us differently than would a grandiose tragic tale dripping with pathos.

For the voiceover, I had this idea of building it as if the thoughts were occurring as the images were viewed, slightly scattered thoughts, as if memories were rising to the surface. It only guides the narration, highlighting what is being said while still leaving the viewer room to assimilate the images for themselves.

What can you tell us about the soundtrack? There’s a little tune that keeps coming back and fading away into dissonance.

It was my brother who composed the music. I wanted there to be, as there is in the point of view, a sense of distortion, for the musical

layers to reinforce the deconstruction or shift in the point of view.

I also wanted there to be a musical unease to accompany my mother’s progressive disillusion.

The same process is felt in the roundabout scene, a contamination or confusion between image and sound. My aim was for the viewer to be with my mother, in her solitude, in the feeling that life is slipping away before our eyes and we are powerless to stop it.

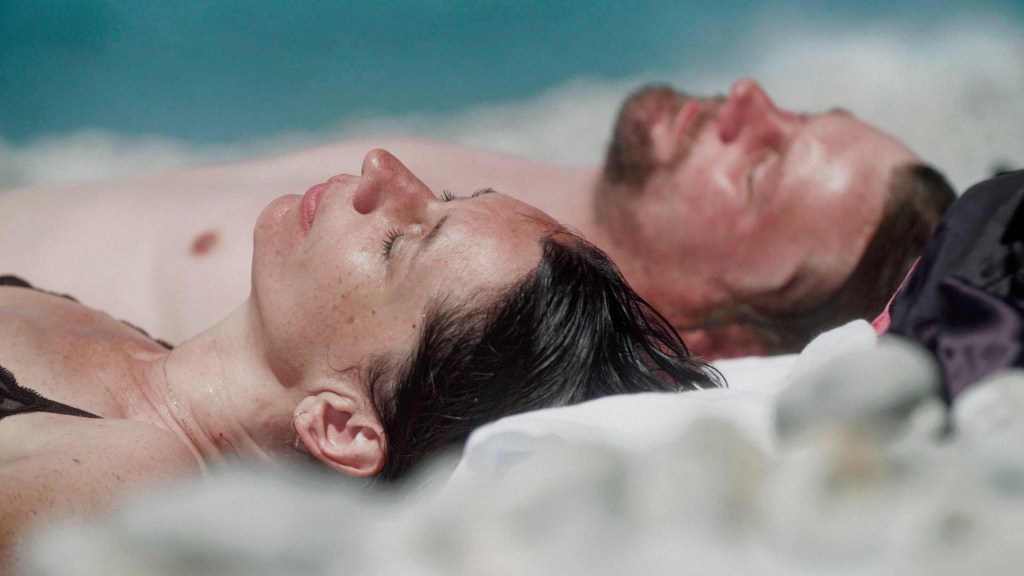

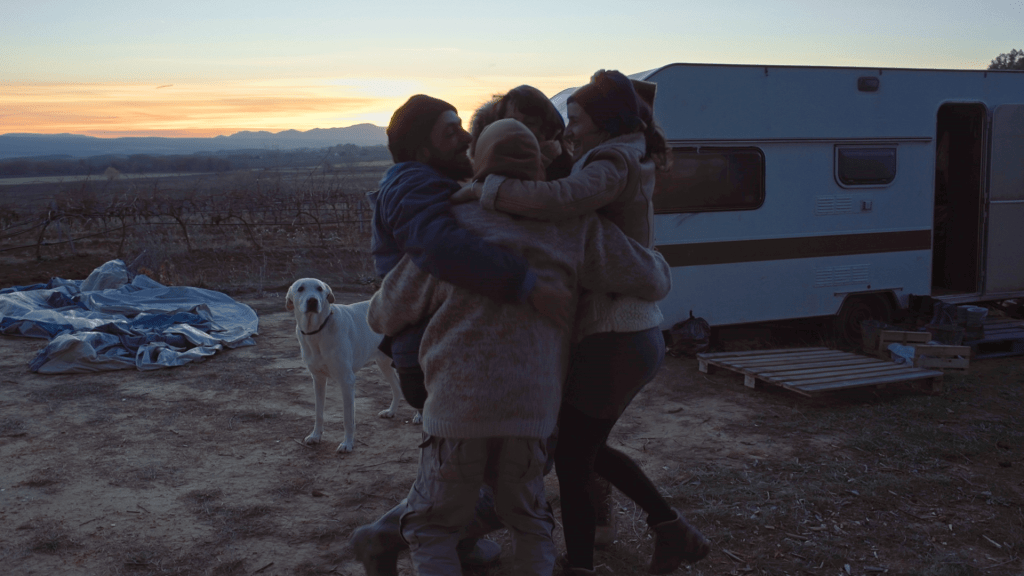

What is the meaning of the final scene?

I filmed that scene without knowing that it would be the final image. It was the editor, Cédric Zoenen, who had the great idea of using it for the ending! It is one of the only shots where all four of us are in frame together. And though the whole path of the film is to move out of images and get back into life, here, we have a deliberately staged scene but now there is no one behind the camera! And it is no longer of any importance.

Leave a comment