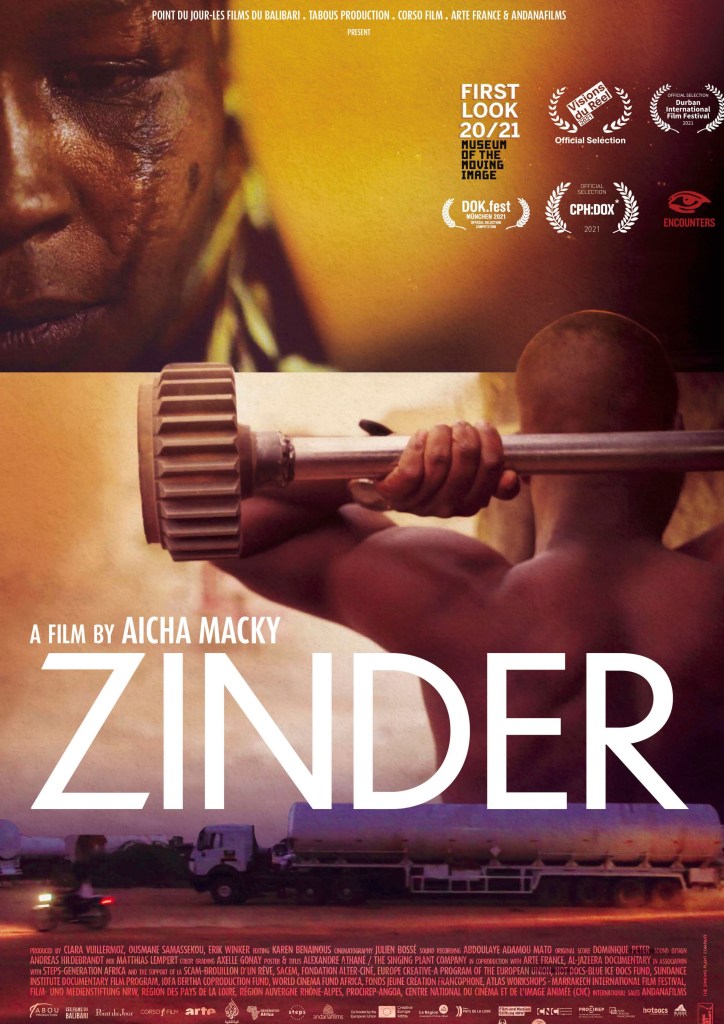

Aicha Macky – Director’s Statement

In 2004, I left my native Zinder to pursue a university education in Niamey, over 600 miles away, where I now live. I developed a distanced relationship with my hometown through short stays to visit my relatives who remained there. Zinder seemed far away, but hideous and even shameful echoes reached me —gang rapes, street battles, armed robberies, all sorts of crimes and tracking— news that seemed like a horror story to me who grew up in that ever so quiet area at the crossroads of Sahel and the caravan trade route. This was an area where different communities (Tuaregs, Hausas, Kanuris, Fulas, Muslims, Christians…) used to live in peace, although the whole society was already consumed by social divisions.

My awakening came in January 2015 as I read a piece of news in which our Minister of Interior commented on a Boko Haram flag spotted during the riots that broke out in Zinder.

Youths belonging to the so-called Palais gangs were blamed. For a decade or so, hundreds of gangs have been thriving in my hometown. Their surrounding world is a poor country (the very last in the UN HDI ranking), its resources plundered by foreign realms, a country with very poor work and life prospects, an extremely unstable region with terrorist movements at the borders of Nigeria (some 60 miles from Zinder), Chad, Mali and Algeria. And a country that has become the last border with Europe with its so called “hotspots” stopping would be exiles from leaving the continent. Many people thus end up stranded in the Sahel region, which makes the local situation even worse.

Be feared and fight in order not to die. Palais (palace) refers to where the Sultan lives, who is the highest civil authority in the city. By naming themselves like that, these youths want to assert themselves as an authority. The gangs challenge the state, are an anti-state. They are a time bomb waiting to explode.

How to chronicle your own people, yourself, your hometown, showing how a haven of peace turns into an idle city, pointing to remedies, trying to heal the wounds and the wounded while letting those concerned speak for themselves, to experience the present time with more hope in a city searching for safety — all this was a dangerous mission for a filmmaker and her team. It took me months to get accepted. Now I am.

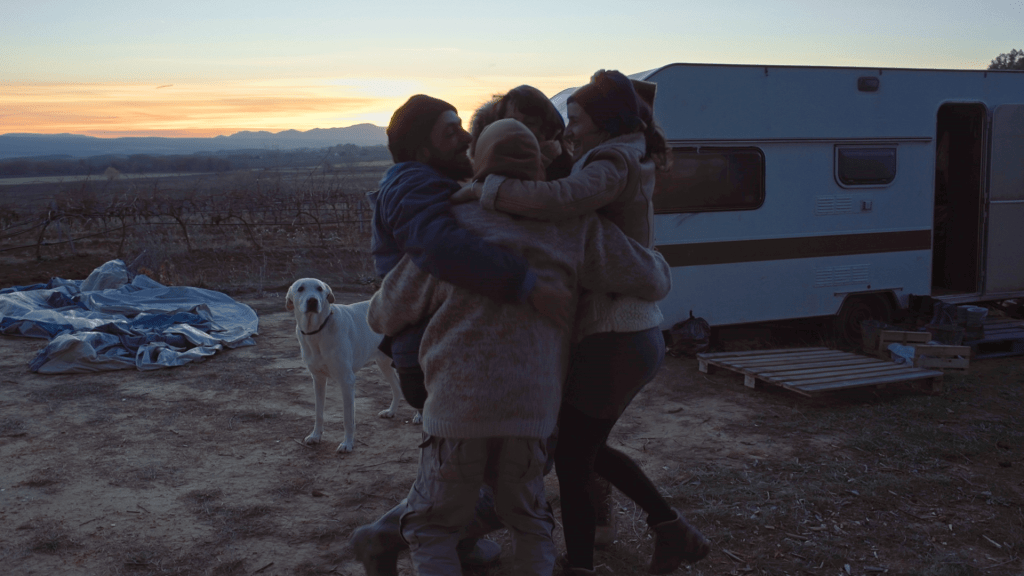

Siniya, Bawo, Ramsess, let me enter their own world. They have a foot inside (the gang) and a foot outside because they want to quit illegality. They have that perspective which allows us to discuss their ways of thinking. They are open to sharing their daily life and survival strategies with me. And above all, being around them keeps changing me.

I understood that Kara-Kara could exist anywhere and is just a reflection of our collec- tive behaviors and the result of a divide: them vs. us.

I was born in a humble family, but on the right side of the tracks, the other side from the opposite neighbourhood, with dim lights. As a child I watched them from afar. Now, as a filmmaker, sociologist and activist, discreet as a shadow, I decide to venture around that dimmer opposite hill, across that border that keeps us apart, them and myself, and bring their

Leave a comment