Director Notes

I started working on this film by searching for stories from a disaster, trying to understand and come to terms with unfathomable loss: What do you do when you have lost everything, your home and someone close? How do you cope? I initially travelled on my own and stayed at the different tsunami struck towns in Japan. I gradually got access to people and places through a process of chance combined with meeting local aid organisations.

Following in the traces of earthquakes, nuclear disasters and ocean pollution, I’ve sometimes been struck by a fear of the future. When I started to film the Fukushima nuclear power plant was still leaking radioactive water into the ocean. Ocean trash is part of a collective narrative that feeds our fear of the apocalypse.

What can I do about it? How can I live in a world where this threat exists? Should I stare at it, being constantly paralysed, or ignore and avoid? What can I do, in my lifetime?

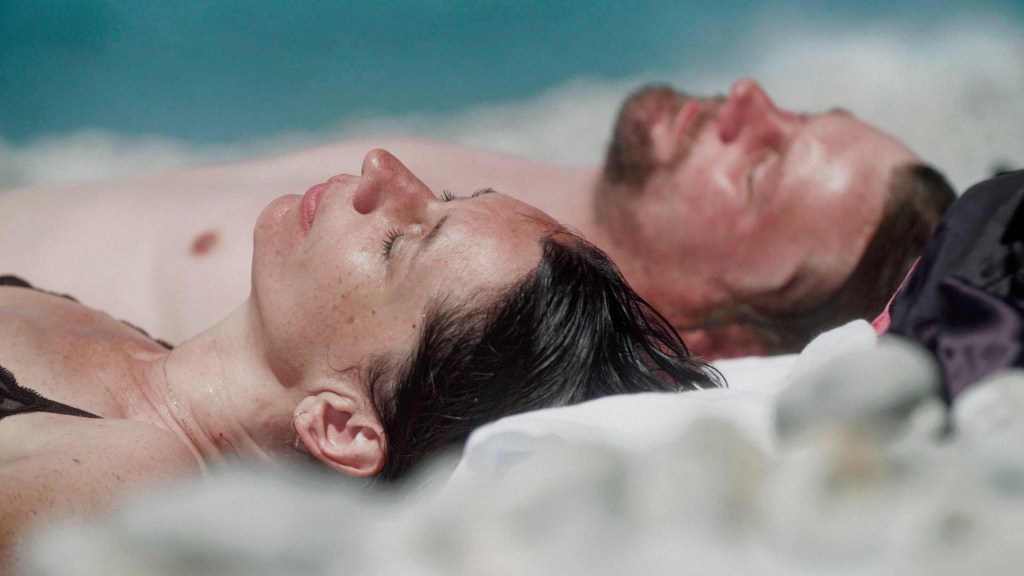

I don’t have an answer to this; I have come to believe there is none. The problems are too complex and multifaceted for a straight answer, but there are clues on to how to live with the questions. On the beach of Hawaii, where the tsunami debris floats ashore, and in Japan, people are living a collective trauma, and at the same time all being part of healing from it. The volunteers are helpers and don’t expect anything in return; they want to help, but do it anonymously. With this film, I hope to encourage the one who watches it to not stop believing that they can help and change.

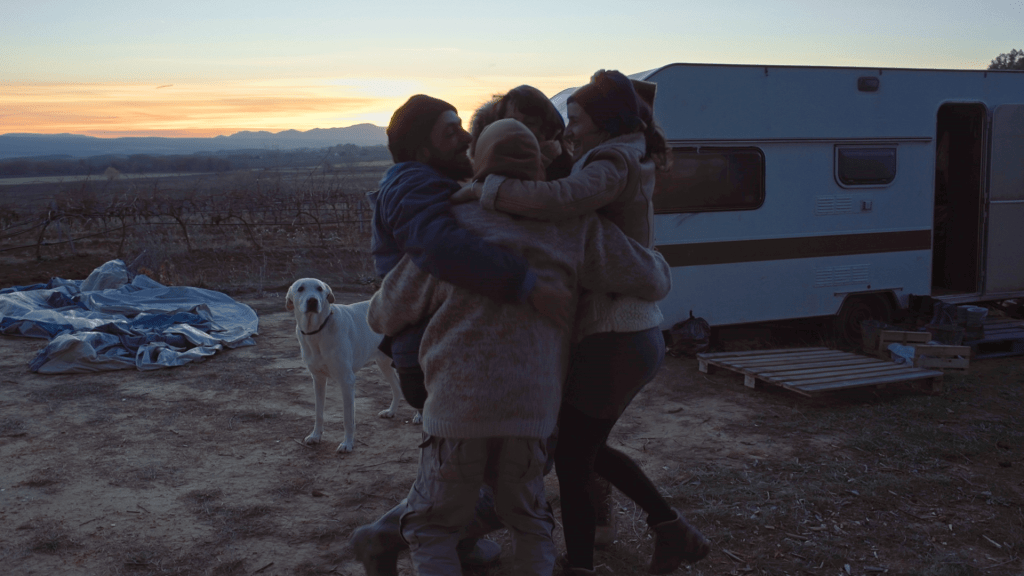

While spending years of collecting stories of disaster and death, to my surprise I realised I was finding stories about love. Learning that people we lost can still be within us, become part of us. To know death is part of the privilege of being human and so is to know love.

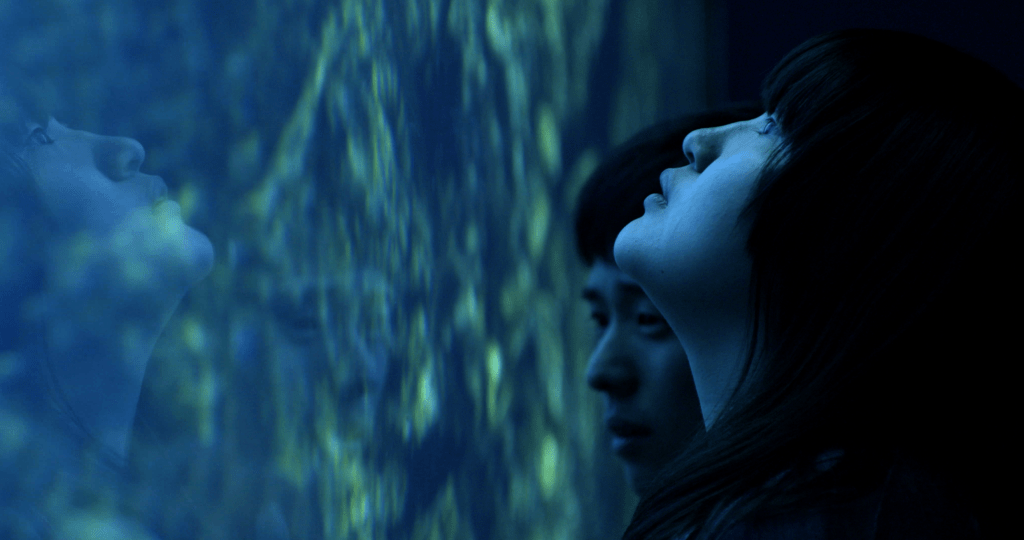

Sachicko keeps writing to her husband for years after he is gone. Yasu dives to find his wife. Ancient myths in both Japanese and Hawaiian cultures speak about the life of the soul after death, creating metaphors for understanding loss.

I want the stories to give a human scale perspective. I think of this film as a chronology for those who grieve, were I want to show examples of how life moves on. I wish the audience to leave the film with the certainty that as the world keeps turning so does the life of the one that survives.

Throughout the whole filming and editing process I worked closely with three interpreters that were Japanese but had the experience of living and working in Europe. They would not just help me to communicate but also advise me on when things were culturally different, sensitive or even inappropriate.

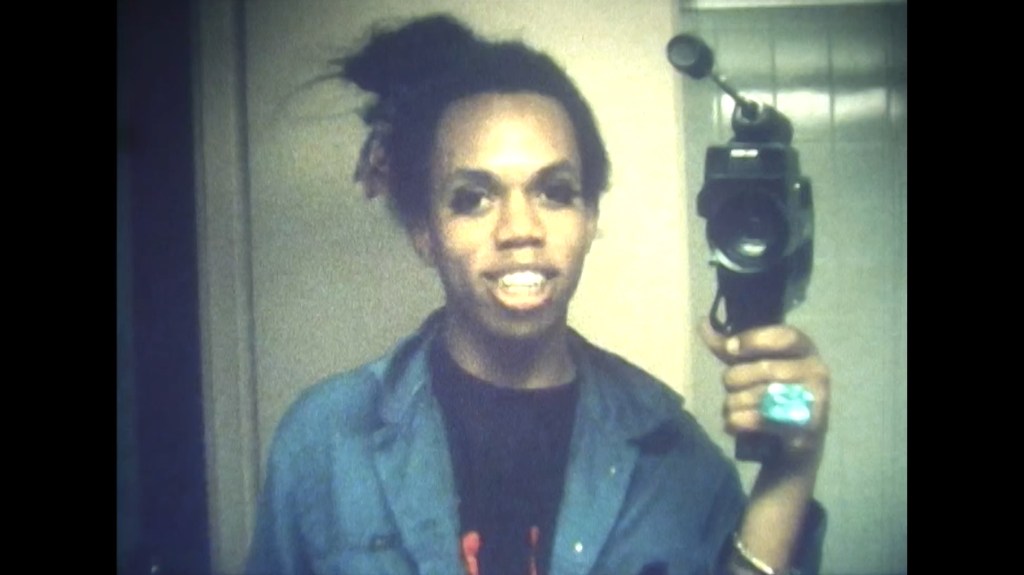

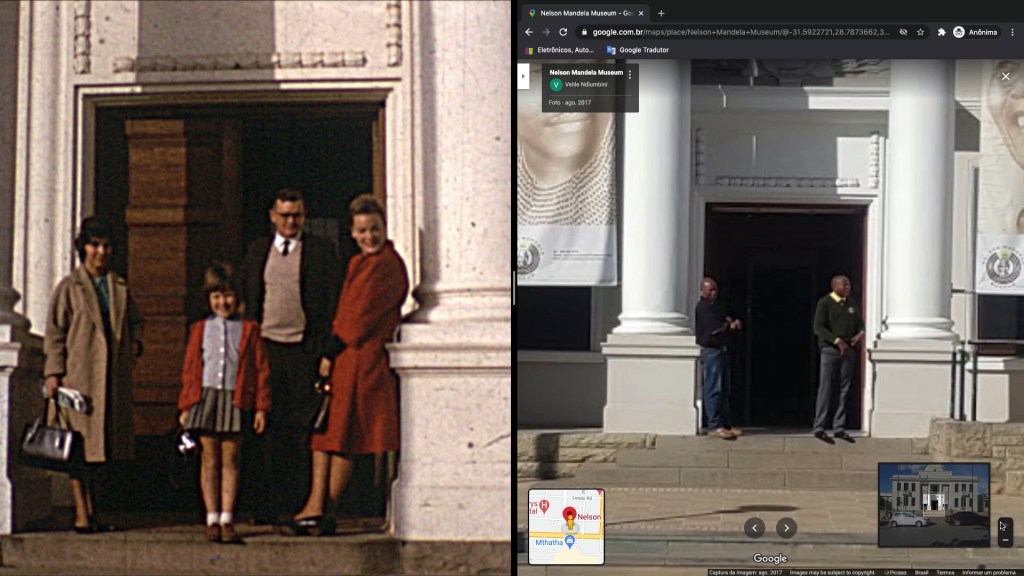

I knew from the very beginning that given the conditions of the production: I would be working in a language that I barely spoke (Japanese) which meant I would have limited possibilities to build direct relationships with the characters. In my initial research; when I travelled on my own and with a translator, searching for stories, I met with many people living through unresolved traumas. I understood that I wouldn’t have the cultural understanding or tools to work with someone who hadn’t already externalised their story. So that became my first rule: that the character I wanted to depict had already told their story publicly. So as I met the characters and continued filming that dictated the choices of characters and how I conducted the interviews; Yasu has told his story several times in international and national press, Sachiko published her poems and was interviewed in Japanese media, Satoko had made a theatre play about her story. I also knew that this meant that I would tell their stories as an outsider -to the outside world and that it would be less like their actual stories but more about their ways to cope. But I would tell it together with them, this made me realise that what would make the film unique would be the combination of the characters and their stories and how they belong together as a whole.

Jennifer Rainsford, Oct 13th 2022.

Leave a comment