Courtney Stephens talks about her films Mating Games, Ida Western Exile and The American Sector (co-directed with Pacho Velez). Interview by Carol Nahra from Docs on Screens.

Did anything surprise you about the making of the American Sector, as you came to dig deeper into the stories behind the placement of these bits of Berlin Wall throughout America?

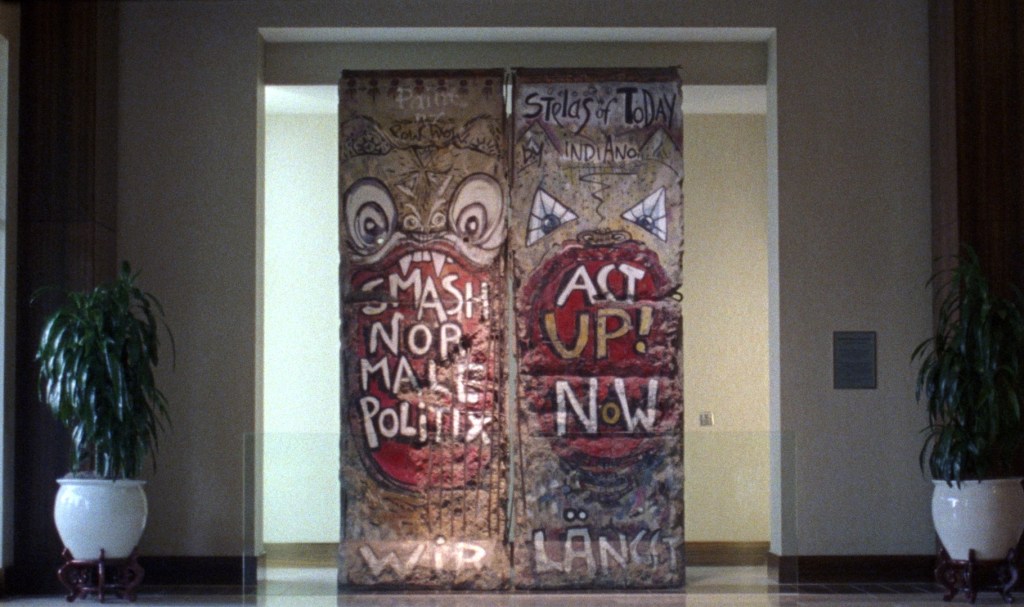

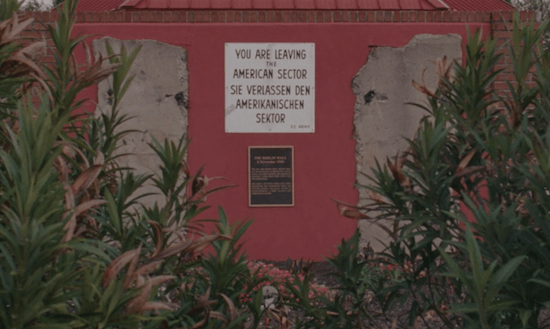

Courtney Stephens: There were definitely some zany installations that we wouldn’t have predicted – a few of which didn’t make it into the film. a slab of the wall installed behind a urinal in a Las Vegas casino for example. There was a kind of eccentric logic to the placements – whether it was in an art collection at Microsoft or in a presidential museum or in some guy’s yard in LA, the wall was there to confer a sense of time and gravitas. The object’s formal qualities – this three ton piece of decomposing concrete – lends itself to that. But I don’t think I could personally say that I find any of the installations tasteful. Even when there is the invitation to contemplation, the fact of it having been brought all the way to the US has an inescapable overtone of domination, like, your national border is now my lawn ornament – I bought it. What probably surprised us more than the fact that so many institutions were in possession of these pieces were the attachments individual civilians found to them, which were far more idiosyncratic and often quite touching.

How did you find all of the pieces of wall?

CS: There were some lists floating around on the internet, but we learned about quite a few of them from other institutions, or just people we knew. A film director I used to work for told me there was one on the Warner Brothers backlot in Burbank. I thought it must be a prop or something, but he was right – a half size piece dedicated to the free flow of information and media, something like that. Another one that didn’t make it into the final cut of the film, though I think it’s there in the footage that plays during the credits. We tried to do a fairly exhaustive inventory of all the pieces, even the ones we weren’t able to shoot, for this article for Cabinet magazine:

https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/64/stephens_velez.php

Since finishing we’ve heard about a few more.

Woven together they paint a fascinating portrait of the US. In what way do you see it telling the story of America?

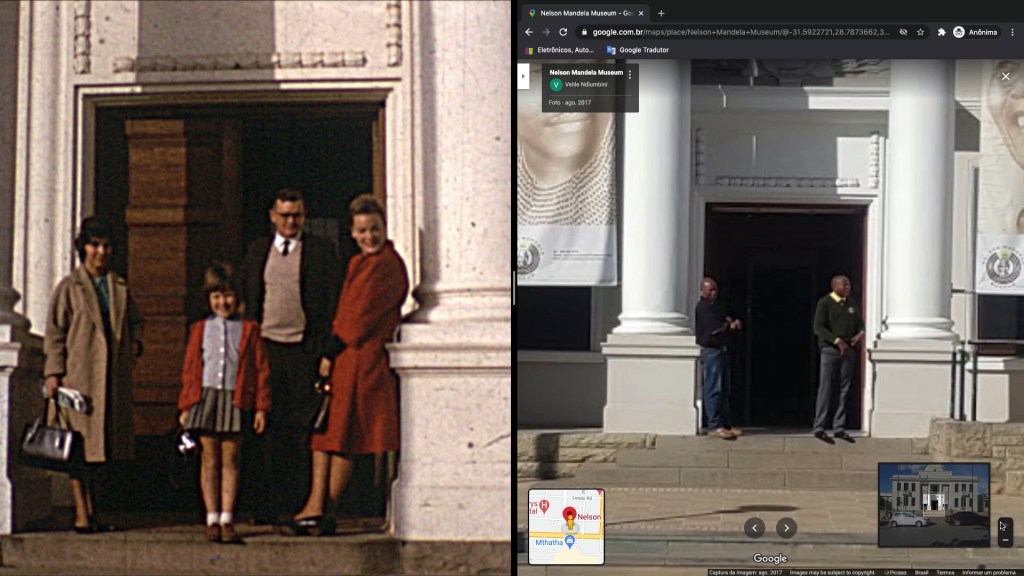

CS: I think the film captures the restlessness of the country at this moment, or in the moment that it was shot which was during the first three years of Trump’s presidency. Going in I think we made some assumptions about the way that people would talk about the Wall based on their political leanings – we were maybe envisioning the country like the blue state / red state maps they play on the news during the elections. What surprised us and helped to sketch out a more interesting picture of the country comes down to the highly emotional way that people relate to the idea of the past through their own pasts. All these private attachments. Even my thoughts about the Wall are linked to watching it come down in my childhood living room, and everything else in that room that also no longer exists. The film ends up being this patchwork that kind of maps out a constellation of the history and meaning of the Wall itself, but speaks much more to the tapestry of US identities and how various people see themselves included in the idea of America. Private experience is so deeply intertwined with political attachments; it’s a stiff mixture when it hardens.

Probably the biggest surprise was the division that cut along generational lines. The Wall fell just about 35 years ago, so for about half the people living now, the Wall symbolizes an international order they had perhaps once understood themselves within. For others, like me and Pacho, it mostly represents the moment of its coming down, and then for younger people they learned about it in school, as history. How do current events get transformed into history? It’s this last group who has the privilege, in a sense, of forgetting about the wall, of continually asking “but what about X”. So maybe the film captures a restlessness within the country that cuts in both directions: the restlessness for America to look at its own failings, or the restlessness to just return to a time when there was a sense we didn’t have to.

What was the most memorable aspect of this shoot? Did it inform any of the work or thinking that you did during the pandemic?

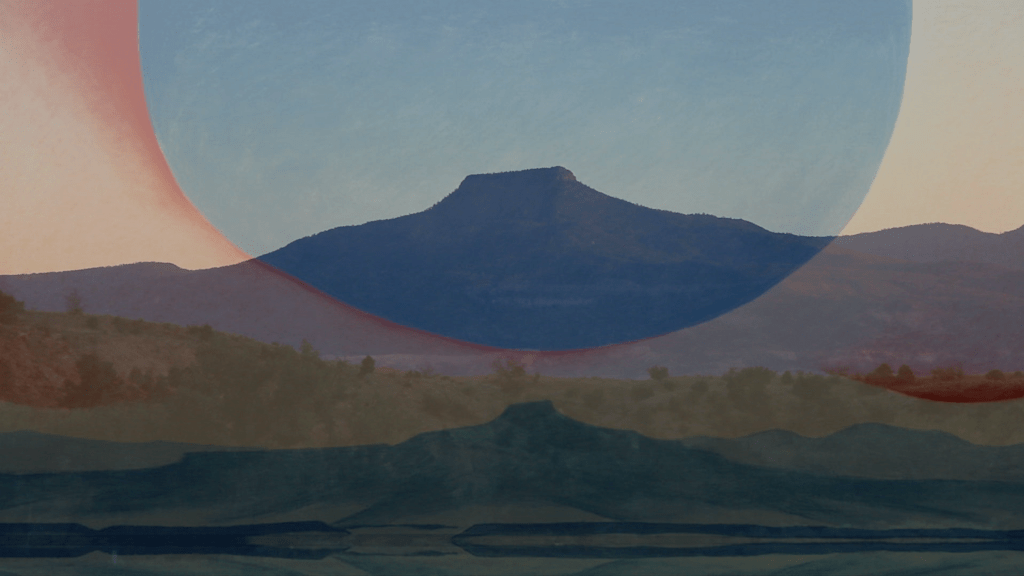

CS: We got to see so much of the country while shooting this movie; I’m currently working on a film in Kansas that came out of spending time driving around in the Great Plains and some of its mythologies. But maybe the lasting effect was the access this subject gave us to large American institutions who possessed these pieces, and how humbling it was to take on such a subject of such large historical scope, but then to find that the film functions on the basis of intimate details. It taught me a lot about working with large ideas and trying not to get overwhelmed. In my short film I try to stay with the details, but to see if I can keep larger ideas tethered to them. Any film, regardless of subject matter, is only ever working with the present moment.

The integration of different types of media and archive in Ida Western Exile is fascinating. How did you approach the making of this film?

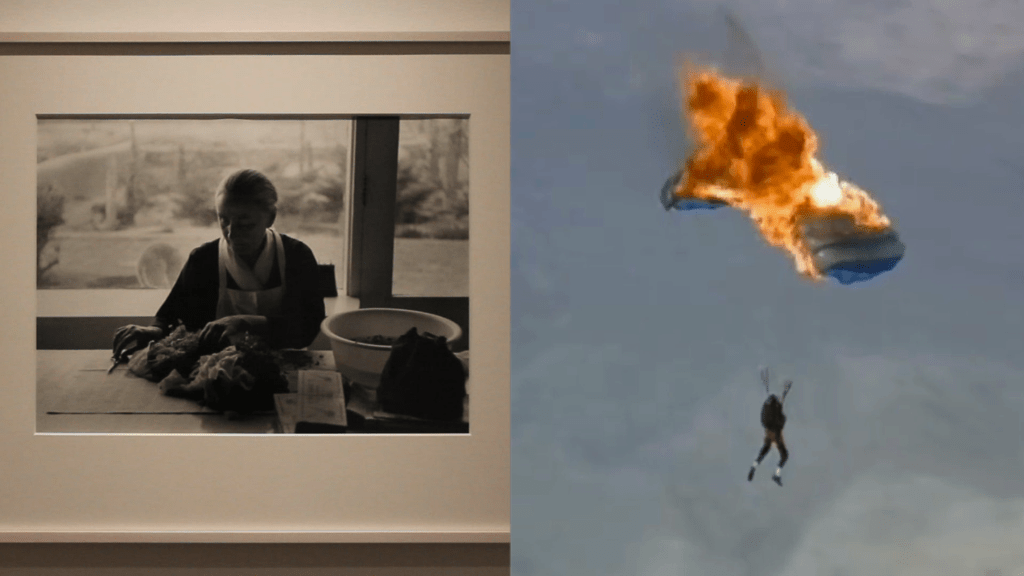

CS: Thanks. I think the use of found material came out of my own experience of casually researching O’Keeffe on the internet, and then thinking about that mode of yearning and wasting time. I’m curious about how we relate to the legacies of artists from times with different media and levels of media saturation. It makes it hard to understand our own live on the same terms as they lived, I suspect. And then the way we tumble through the evidence on the internet, that process that can even give a taste of personal momentum but is often just a kind of rut.

The framed pictures of O’Keeffe were filmed at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, but the archival footage is collected from TV specials and documentaries that ended up on YouTube. I really can’t remember how that parachute-on-fire footage turned up. So I guess I was observing my own time-wasting and wondering if that wasn’t relevant to the way we get stuck in our desire for role models. I never really had any.

What do you see as the link between Ida Western Exile and Mating Games?

CS: Hmm, I don’t know. I guess they’re both about the impossibility of reentering the past? Mating Games is this almost painfully idyllic vision of youth and trust falls and hyper-binary gender. And would I want to spend a summer on that beach? I don’t think so, honestly. But that iconography is still selling fantasies. Incidentally, my dad grew up on the beaches of LA pretty much right around that time and just a few miles South, so it holds a different meaning for me, this heavy Americana.

Can you talk about your approach to discovering and repurposing old archive? How and where do you find inspiration?

CS: That’s a nice question. I can become fixated on almost anything as having the potential to speak in a very different way than it was intended to. I am thinking of a hard drive I have where I have this fantastic old educational film on the way lakes age, some how-to videos on shop maintenance, and other stuff. I like the idea of finding some overlooked elements of something, like the unconscious of the thing. It’s about ship maintenance but there’s something going on here in terms of the American male, maybe. Or like, the ageing lake is also me.

Leave a comment