Emanuel Licha | Director’s Note

An important part of what I envisioned for zo reken has to do with an episode that I experienced almost thirty years ago. I was back then a graduate student in geography and I was participating in a research project in a West African country. On the day of my arrival, I embarked with the team leader, white as I am, for a tour of the city onboard his 4×4 vehicle. It was the end of the rainy season and the dirt roads were gullied. The robustness of the vehicle allowed us to travel at high speed on the corrugated roads, narrowly avoiding pedestrians and cyclists. I was discovering the world of “international cooperation” from the air-conditioned cabin of an all-terrain vehicle.

4x4s are objects and spaces which mark the distinctions between the privileged and the afflicted, between caregivers and those assisted, between the “powerful” and the “weak”. The closed cabin of the car is the protected and mobile space of those who come and go, who are there without having to be or needing to stay. Thirty years ago, my repugnance at these objects and spaces, which I could use because I was a White in a country of Blacks, was no stranger to the fact that I ultimately did not make a career in this environment.

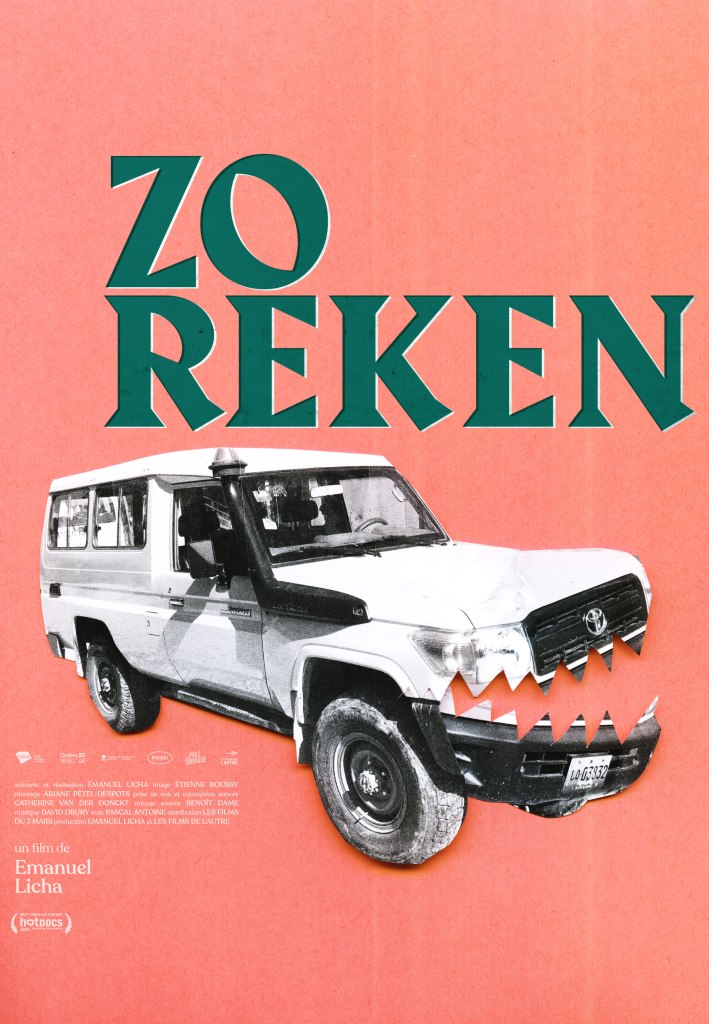

The type of 4×4 vehicles in which I was driven also exists in Haiti: it’s the Toyota Land Cruiser, nicknamed “zo reken” by Haitians – which means “shark bones”- because it is so sturdy. This is the reason why it is widely used by humanitarian aid organisations, which in turn popularised it for other uses: the repressive henchmen of the current president, Jovenel Moïse, who is despised by the people, shamelessly use it to terrorise the population. As the writer Lyonel Trouillot is heard saying in the film, “this vehicle means either NGO or repression. It means power, in any case.” Aid and repression are united in the zo reken, which has become the main character and antihero of the film.

The filming process was guided by the idea of “hacking” the zo reken by diverting it from its initial function, so that it no longer serves to transport humanitarian workers but rather to elicit the voices of those who are more used to see it pass than to travel in it. What was said and heard in it is a scathing criticism of the neocolonialist enterprise which continues to plague the country. That this criticism be framed from within the most emblematic object of this enterprise was an attempt to decolonize the zo reken.

I say “an attempt” because I know that the project carries with it its own contradictions: it is the film of a white man, shot with white men’s means, aboard a white men’s vehicle, in the country of black people. But this is a film aimed – not only but above all – at Whites, as it calls out to them as passers-by did to us in the streets of Port-au-Prince: “Whites! Let’s not play anymore!”. We can hear them clearly in the film.

We can also clearly hear other characters talking to us about the “fatal assistance” and the “stubborn patriarchy” inflicted relentlessly on Haiti. The country is one of the poorest in the world, but we continue to sell it our goods, our “expertise” and our arrogance, including through some lucrative humanitarian aid channels. I am not talking here of the indispensable solidarity that is deployed in urgent cases of disasters or conflicts. I am rather talking about the colonial dikes which have still not given way completely, even if they show signs of vulnerability here and there and sometimes some real subsidence. Inexorably, the lands are getting flooded. May the zo reken get stuck in the mud.

Leave a comment