Interview with director Karima Saïdi by Jeremy Hamers.

Jeremy Hamers: What first struck me in your film ‘A Way Home’ is that unlike many documentaries that tell the story of immigration through a family experience, your film never puts History above the trajectory of your mother, the film’s main character. We always stay as close as possible to one person, Aïcha. She is, of course, a witness and an agent of Moroccan immigration in Belgium. But she is above all a mother, a woman who lived her life freely and whose memories are the guiding thread of your film. These memories are much more than mere pretexts to evoke History. Yet the project began precisely at the moment when you became aware of your mother’s loss of memory…

Karima Saïdi : Aïcha, my mother, fell ill at a time when I rarely saw her. When the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s was confirmed, I quickly realised that I would have to take care of her. That was the starting point for a renewed encounter. I found myself thrown into a role that I hadn’t wanted to take on since I had left home, at least not as Mediterranean families see it: I would have to take care of her. So I started spending a lot more time with her. I literally got to know her and started protecting her. And we found ourselves in opposite roles. I, the daughter, symbolically became the mother. I was very moved by that experience. I was suddenly confronted with her fragility. In other words, she could no longer play the role of a very powerful and strong woman. And it all came down to me just as I was starting a career as a script girl on fiction movies, and had to go abroad. At the time, I read Annie Ernaux’s book, ‘I Remain in Darkness’, a diary about her mother who also suffers from Alzheimer’s. Reading this book was a turning point for me. I started keeping my own diary. And for a year, I observed what was going on. And then the choice to make a film became obvious at that moment; I realised that I was the only one who could make this film. So I started recording her voice, our conversations, and taking pictures.

JH : The film is the recording in images and sounds of a new meeting between a mother and her daughter. But ‘A Way Home’ also gives the impression that this renewed encounter will reach far beyond the private or intimate sphere. For you, this meeting is the starting point for a process of cultural emancipation.

KS : When I made this film, I experienced something very striking. I would never have allowed myself to make such an intimate film in the place where I come from. That would have been impossible for me. My education, my codes, my values forbid it. Besides, I am also an editor, which means that I always work on the films of others. I am the midwife of other people’s films. So, when I started making this documentary, I went through a completely new experience. I was confronted with many questions, simple but fundamental ones. How do you make a film? But also, how do you film your mother? How do you film a sick mother? An ageing mother? I have to face all these questions, and yet my education is based on the sacralisation of the mother, whom nobody has the right to bring down from her pedestal, all the less so when she is ill. Now, these questions were going to be quite crucial for me since they would also allow me to free myself from the injunction, from a series of prohibitions. And then I realised that if I told the story of my family, no one would have the right to blame me for anything. It is our story, hers and mine. And so, the prohibitions that initially made this film impossible were, in fact, our own prohibitions. Overcoming them reconciled me with my culture of origin. Therefore, this film is about my family history. But, inevitably, it is also a film about Moroccan immigration, about the experience of exile, about a woman who went away to live without a man, and who was therefore considered by her culture of origin as an exposed woman.

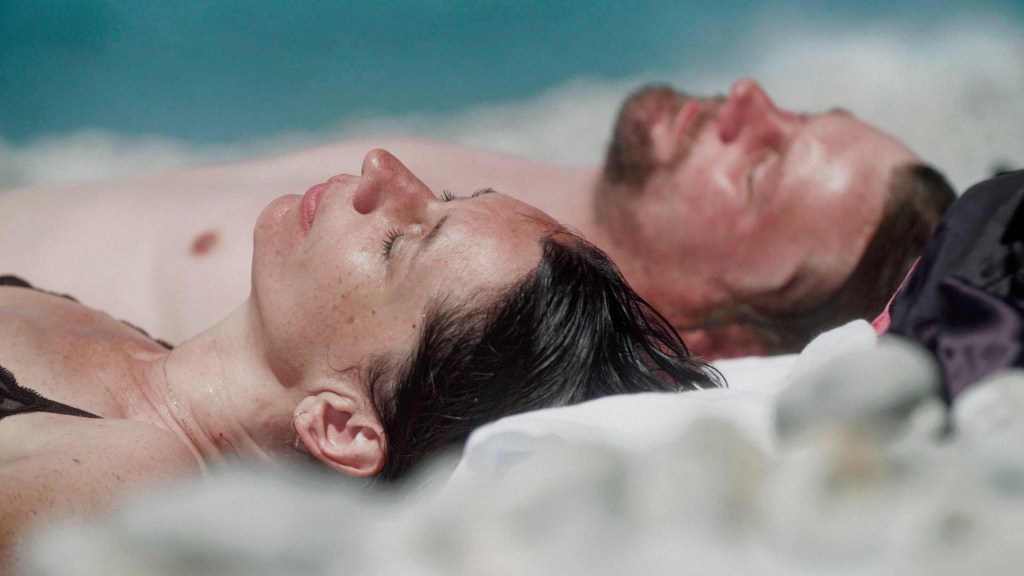

JH : If the film is the result of several stages of emancipation made possible by the disease, it is quite striking that we have to wait five minutes before seeing Aïcha’s face on the screen. And when the viewer can finally place a face on the voice he has been hearing all along, it is through a photograph. Then, other photos follow this first portrait. Through a quick montage of still images, the main character seems as if she were about to start moving. But she never becomes a moving image herself. It is as if something was resisting Aïcha’s transition to film. Not everything can become a film.

KS : I tried to film my mother. I have footage on which you can see her. But it’s too much. Because what I’m filming during that moment is private, it’s not the film. The still image reveals a sort of imbalance. In these images that are not quite in motion, the body is a presence, but one that undergoes a temporal disruption. By superimposing a few still images, I’m looking for a way to reanimate her, to put Aïcha in motion, at a time when everything was coming to a standstill. In the end, I preferred to work on these series of still images, these jerky cuts, because they induce a sense of gap. I couldn’t make this film by capturing my mother in a reality recorded at 25 frames per second. It wouldn’t have worked. It would have been another story. And this way of proceeding is much richer for the voice. You can hear her better. Her voice is always off-screen. Can’t everything become a film? Putting things in motion is bringing them into a narrative, bringing them back to life, making a film.

But I would add: what could be more intimate than a mother’s voice? I didn’t know how I would tell the story based on what I had recorded. When you’re at the same time the director, the mother, and the daughter, you work a lot by instinct. As a daughter, I was still trying to record images and sounds of my mother. And at the same time, the director in me wondered about what was necessary for the film. All the filmmakers I met during the shooting, all those with whom I talked about the shooting process, advised me to film my mother. And I told them it was impossible for me. But they couldn’t understand. In some way, it was easier for the daughter to take photos of her mother than for the filmmaker to film her.

JH : There is one particular sequence that induces a break in tone. That sequence shows children holding the Belgian flag or laying wreaths of flowers in front of the Unknown Soldier monument in Brussels on the morning of November 11th. The vast majority of these children are from immigrant backgrounds. This passage in the film is ambiguous. On the one hand, it seemed ironic to me because it denounces, in a tongue-in-cheek way, the fact that children are often artificially associated with an official story that is not their own. On the other hand, one can also consider that this sequence offers an image of integration.

KS : To me, this sequence is about integration. It answers the question: why did we become Belgians? When, as a child, I had to carry a wreath of flowers on November 11th, I felt very proud. When, as a child, I took part in the November 11th ceremonies, it meant to me that I was part of this society. I don’t see this as artificial assimilation. These are new rituals that are becoming part of the way of life. And making room for immigrant children in that ceremony is fundamental. I attached great importance to this sequence, despite the momentary rupture it creates in the film. Belgium, as a country, has given me a lot. I think you have to be an immigrant to realise that. Had I lived in Morocco, coming from a less well-off social background, my story would have been very different. I was able to study at the National Institute of Dramatic Arts. That would have been totally impossible in Morocco, mostly for financial reasons. Living in a country where you have rights is an incredible opportunity for me. Of course, issues of social determinism are topical in Belgium. And they are constantly on my mind. But I am also aware of everything Belgium has given me. The art studies, the academies, it’s extraordinary.

Of course, I feel a growing need to tackle the issues of contemporary feminism, the body as a political object, etc. The status of women in Morocco remains problematic. Had my mother stayed alone in Morocco with her three children, nothing would have been possible. I would have liked to talk about it with her. I know that, as a single mother, she wasn’t protected at all in Morocco. So I also feel grateful to a country that has given me the tools of criticism. The November 11th sequence goes hand in hand with one of my mother’s statements in the film: “Westerners are more respectful. Moroccans always find something to complain about.” But when I ask her if she prefers to be with Westerners or Moroccans, she chooses the latter. And that is how she lived, in paradoxes.

Brussels, November 2020.

Leave a comment